While today’s crop of computer-wielding mechanics rely on high-tech tools to formulate diagnoses, there’s still something to be said for the tried-and-true technique of interpreting the quantity and color of smoke emitted by a diesel engine.

Learning to interpret these signals is straightforward enough. Black smoke represents unburned or partially burned fuel — the more of it, the greater the inefficiency, as unburned fuel is wasted fuel. There are a variety of causes for black smoke, the most common of which is overloading, also known as overfueling, and occurs when more fuel is pumped into a cylinder than can be efficiently burned in the combustion process.

|

|

Thick white smoke on startup that clears may be normal for an older, mechanically injected engine, but it can be caused by a bad pre- or post-air combustion heating system. |

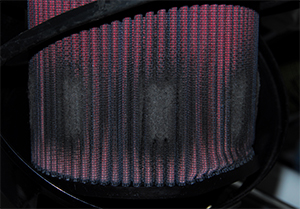

If you’ve ever seen a power or sailing vessel (one whose diesel engine is mechanically governed) maneuver hard while docking or emit a puff of black smoke at the moment of sudden acceleration, this is an example of a momentary overload. If you’ve seen vessels emitting a constant plume of black smoke while under heavy load, this represents a chronic overfueling scenario. This is typically caused by an incorrectly sized propeller, too much pitch or too much diameter. It may also be caused by a fouled propeller, as just a few hard barnacles can induce enough load and inefficiency on a small engine to cause overfueling. Worn-out, carbon-encrusted or malfunctioning injectors, or a clogged or wet air filter may also be the cause of black smoke.

Blue smoke, however, is typically created when crankcase lubricating oil is burned in the engine’s combustion chambers. Not only does this create an unpleasant haze that follows the vessel and fouls its transom, but it represents oil consumption as well as carbon formation within the combustion chamber.

|

|

A fouled air cleaner can restrict oxygen and lead to black smoke. |

Blue smoke is typically caused by worn valve stems or guides (stems are part of exhaust and intake valves, while guides are the tubes in which they move), worn or carbon-fouled piston rings, or a leaking turbocharger shaft seal. Because oil is a much heavier distillate than diesel fuel, it does not burn completely, which is what causes the carbon formation and blue smoke. Determining which of these is the culprit — valve stems, guides, piston rings or the turbo — calls for a cylinder differential leak-down test performed by a diesel mechanic, or an inspection of the turbo and aftercooler.

White smoke is among the most difficult symptoms to diagnose, primarily because there are so many possible causes. They range from overcooling, whereby the cylinder head and combustion chambers operate at a temperature that is too low, leading to poor combustion characteristics, to piston ring blowby, which in turn leads to low compression and poor combustion. In most cases, white smoke represents atomized unburned fuel or very small droplets of fuel — a fog of sorts. It’s common and normal to see this when a cold engine is started and until it warms up. If, however, pre- or post-heat devices such as glow plugs or air intake heaters are malfunctioning, white smoke production may be excessive and long-lasting.

|

|

Carbon-encrusted, worn-out or damaged injectors produce poor spray patterns where fuel is inconsistently atomized. |

In extreme cases, the engine may be difficult or impossible to start. Poor quality fuel, particularly fuel that is “off spec” or not within the parameters set forth by ASTM standards for No. 2 diesel fuel, will exhibit poor burn characteristics, which in turn may lead to white smoke production. Adding a fuel cetane booster may temporarily alleviate this problem while identifying its source. Other causes of white smoke include poorly adjusted valves or worn valve seats; a partially activated decompression lever; a blown head gasket allowing coolant to leak into the combustion chamber, an indication of which is falling coolant level; and a cracked cylinder head or cylinder liner. All of these can be identified by a competent diesel mechanic who has the right tools in his or her bag.

|

|

Worn valve guide seals allow oil to migrate into the engine’s combustion air supply and burn in the combustion process, leading to blue smoke. |

A final cause of white smoke is incipient overheating. In some cases the smoke is actually steam, and the insidious nature of its production is that it occurs in the exhaust system rather than as a result of an overheating engine. If the flow of water into the exhaust injection elbow is compromised or restricted, it may become excessively hot, which in turn can produce water vapor or steam while still not being restrictive enough to cause a wholesale engine overheat. This possibility can be identified by measuring the temperature of the wet portion of the exhaust (the hose) immediately downstream of the injection elbow using an infrared pyrometer (or one’s hand, carefully) while the engine has been at cruising speed for at least an hour. It should be well below the ABYC-specified 200° F threshold for exhaust systems and typically in the 130° to 150° F region.

Steve D’Antonio owns and operates Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting, Inc. (stevedmarineconsulting.com), providing consulting services to boat buyers, owners and the marine industry. He is an ABYC-certified Master Technician.