Cruising for over two years in the tropics of Southeast Asia has wilted our sea legs. We have experienced nothing more adventurous than an occasional sudden thundershower as we ghosted the coast of Borneo and all the shores of Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia. Now it is time to get back to serious passagemaking and prepare to zigzag our way across the Indian Ocean from Malaysia to South Africa via Madagascar and many remote islands in between. Once again, we will be in belts of strong weather. In the Indian, yachting facilities are few; the boat must be in solid long-haul condition. When we depart Malaysia, we will be ready for real sailing — though the preparations have been a year in the fixing.

Owning one’s own long-range cruising boat is the only way to access some of the most remote specks of land in the world, like the Pacific’s Holmes Reef, Minerva Reef, Bikini, Suwarrow and Fatu Hiva. Now, heading out to the Indian Ocean, we cannot miss the chance to visit the fabled Chagos, where no one lives but the largest coconut crabs and seabirds on tropical islands with countless fish on the clear reefs. Departing Malaysia, our water and fuel tanks will be full, including all our deck-stowed jerry jugs. Since there will be no cheaper fuel on our horizon, some of the five-gallon jerry jugs are one-time-use disposables.

Months of food stores

The waterline of Brick House will be further depressed by months of food stores. Food throughout the Indian Ocean is expensive, so we are stocking up in Malaysia. As we move south in latitude and into known windy areas, our load of supplies will lighten so we will become more buoyant, agile and seaworthy. As we work our way to Madagascar, where aggressive storms are a near certainty, we want to be as unencumbered and nimble as possible in order to lift and move on top of the waves, not be washed over and beaten by them. At that point, we want on our boat no more than 50 gallons of water and no more than 40 gallons of diesel in the main tanks with the remaining deck-stored jerry jugs to be empty.

|

|

For the Indian Ocean crossing, the Childresses bought a new Mack headsail. |

We have worked hard to remove the hatches and portlights, resealing them to stop present leaks and ensure there will be no new leaks. Cracks in the side decks were ground out and repaired. The not-so-clear plastic of the dodger windows was renewed. A new mainsail cover is now in place, and all the rigging has been inspected. The hull has been cleaned with new antifouling applied. These are all parts of the maintenance treadmill any cruising boat owner must endure. But to successfully sail us across the Indian Ocean, we decided to order a new genoa.

To move us through the calm weather latitudes to Sri Lanka then southward to Chagos, we have on board a new 125 percent genoa from Mack Sails, located halfway around the world from us in Stuart, Fla. We have personally visited some of the lofts in Southeast Asia and have concluded it is better to buy American. Our new genoa is made of 7.77-ounce Challenge Marblehead Dacron. According to Mack Sails, “These fabrics are the finest, most tightly woven fabrics in the world and rely on the quality of yarn and weave, rather than impregnated resins, to maintain integrity.” To distribute loading more evenly across the fabric on the genoa, and to hold the sail shape for 15 to 20 years, Mack sews their jibs with the more difficult miter panels rather than the easier to sew, long, crosscut panels. As we work into the stronger wind areas, we will replace the new 125 percent with our 90 percent jib made of 8.77-ounce Marblehead. These sails, along with our tough little cutter sail also made by Mack, give us the versatility needed for working through known soft and strong wind latitudes.

A new anchor

After the sails, our thoughts turned to anchoring. Ten years ago, a 60-pound CQR was our primary anchor until it showed how it could plow a long farmer’s furrow and still not dig in. That anchor nearly ended our voyage soon after it began. The 66-pound Bruce became our primary anchor, and it has served us well in all sorts of anchoring conditions for the past 10 years. But the Bruce was not infallible. We wanted to keep up on the latest anchor technology, so we felt an anchor with a more pointed entry would bury quicker and could hold as securely as the Bruce normally would and possibly better. We decided to replace the Bruce with a 60-pound Manson Supreme anchor, which is made in New Zealand. Because of their sailing environment dipping into latitudes of the Roaring Forties, New Zealanders know how to manufacture their yachting products to withstand harsh conditions. I don’t want to risk having gear on our boat made in China. So far, the Manson Supreme is performing flawlessly.

|

|

The Childresses also purchased new Henri Lloyd foul weather gear. |

In the tropics, when a heavy downpour or sea spray breaks over our boat, we have been slipping into a cheap plastic raincoat bought at a hardware store in order to stay dry. Our “ocean” designated foul weather gear has always leaked right through the “breathable” fabric. Now we have gotten serious about foul weather gear that will do what it is advertised to do. Our research brought us to Henri Lloyd’s Freedom line of foul weather gear, which is made of polyamide coated with polyurethane. I recently tested this gear on a yacht delivery from Rhode Island to St. Maarten and it was impressive. It kept me warm and dry, and it was not cumbersome to put on or take off. There are plenty of pockets in the right places without overdoing it. An interesting highlight is the hood, which gives full wind and spray protection and can do this without ruining peripheral vision. The hood has a clear Optivision high-visibility hood system.

Navigation resources

At our navigation station, we have a Raymarine eS128 chartplotter with a 12-inch screen. Not only does the large screen have the advantage of being viewable all the way back to the helm, but it gives us a much better spatial awareness than any of the smaller screens that preceded it.

There is nothing like having a large-scale paper chart, however, to see where a boat has been and where it is going. The distances in the Indian are so great, we ordered a paper chart from Bluewater Books and Charts in Fort Lauderdale that covers all of the Indian Ocean. That chart will be folded flat and live under the Plexiglas of the chart table. We will be able to quickly plot the location of fellow cruisers and keep track of our own wanderings.

|

|

Cruising guides from Bluewater Books and Charts. |

Additionally, as we start the second half of our circumnavigation, we have found that — despite the digital plethora of information — a printed paper cruising guide is still our preferred way to organize routes and anchorages ahead. Bluewater Books and Charts has been in business for more than 30 years and offers the single greatest selection of paper and electronic charts, cruising guides, marine books and publications, software, flags and instruments available for sailors like us. We stocked up with the Indian Ocean Cruising Guide, East Africa Pilot, South Atlantic Circuit and Patagonia & Tierra Del Fuego Nautical Guide. Rebecca has also made KAP files (Google Earth charts) for every possible stop along the way. We can now go into anchorages with full satellite images; but, at our fingertips, we’ll have all the paper books and information we need in one central location without having to turn on a computer.

Getting weather info

Getting accurate, economical weather routing reports and communicating with those back home while we are far away from land has always been a challenge. On previous ocean crossings, we relied on our SSB radio and Pactor modem for email and weather. Sad to say, that trusty equipment is becoming equal to using a cassette player when an iPod is available. Although there is still a use for the SSB radio for communicating on a schedule with other cruisers, its other functions are waning.

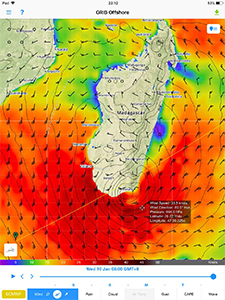

We have signed up for an Iridium GO marine package with PredictWind. Iridium GO is a new-generation Iridium satellite Wi-Fi hotspot to which all our hand-held devices can connect. PredictWind also offers a myriad of downloadable weather products, including weather routing, with intuitive feature-rich software to retrieve and examine the reports it offers. But, better than using this application via a cantankerous SSB, the Iridium GO — with an external antenna — offers the best value and least complications for downloading weather and email while on a passage anywhere in the world. It’s not faster than SSB/Pactor, but it is available around the clock when we want it. PredictWind controls all of the connections to the GO, and the two are so completely integrated that one would almost think they were using the application on the Internet, albeit more slowly.

|

|

The PredictWind package can show ocean currents and much more. |

We will be able to receive and send emails, as well as utilize 150 minutes of voice time per month to be used through our smartphones for family issues back home, emergencies, ordering of parts or technical support at sea. We paired this system with another product from RedPort called XGate to add more functionality when using our laptops both through the GO and when connected to the Internet via other means. With such interoperability and so many advantages, an entire article could be written about the combination. Month-to-month contracts for service, if purchased through the PredictWind website, allows shutdown to a minimally priced plan while in port.

Another great feature of the GO is the SOS button. This is not a substitute for a stand-alone EPIRB, but it is a great additional tool. GEOS Safety Solutions provides free coordination of efforts in case of an emergency, as well as affordable search and rescue and medevac if the SOS button is pressed during an emergency.

Charging EPIRB batteries

Recently, we hand-carried our ACR self-deploying 406-MHz GPS, EPIRB and smaller PLB on airplanes from Malaysia back to the U.S. With the batteries in the equipment, we ran into no concerns by airport inspectors. The batteries have a long shelf life even after their six-year expiration date, but we want to take no chances. In the U.S., we sent the equipment to ACR in Ft. Lauderdale. After changing the batteries, they were mailed to us at our departure address in the U.S. so we could hand-carry them back to Malaysia. Monthly, we flip the switch halfway on our EPIRB to activate the self-test mode in order to be sure it is successfully acquiring satellites and transmitting to the test-receiving station properly.

|

|

ACR EPIRB showing a successful self-test. The unit also shows its status should it be activated in a real emergency. |

Prop fouling

I have never been able to keep antifouling on any propeller that was installed on Brick House no matter what material the prop was made of. Antifouling quickly disappeared, which meant the beginning again of the biweekly chore to scrub the marine growth from the prop and drive shaft. In the 85-degree tropical water to which we are accustomed, the work was not terribly challenging. However, there are frigid waters in our future, which even layers of wetsuits can’t entice me to go in for a casual prop cleaning. Cruising friends who have used Propspeed, which is a silicone coating, are very satisfied. The application is a very precise process of sanding, cleaning, etching, applying primer and then the final application of the clear silicone coating. The clear coating is not antifouling but an ultra-smooth surface that marine organisms have a very difficult time attaching to. If organisms do settle, they are easily brushed off. The manufacturer of our Kiwiprop suggested it is not necessary to prime the Zytel blades before applying traditional antifouling or Propspeed. Following those directions, I have never had success with antifouling staying on the Zytel blades for an adequate amount of time.

In treating the Zytel blades, I followed the Propspeed directions in the same process as for the stainless steel components except for the etching. With a Kiwiprop however, an applicator must be careful not to build up any material in the area of swing of the blades’ trailing edge, as this could inhibit their forward-to-reverse function. Propspeed is another great product made in New Zealand; there are imitators, but only Oceanmax makes Propspeed and has a long positive track record.

A major safety item is the disappearance of the nonskid on our side decks. Since they were painted nine years ago, our decks have gotten slippery over the years from the wearing away of the sand nonskid embedded in the deck paint. Where we are going is not a place for unsure footing. There are three grades of nonskid sand: fine, medium and coarse. We used the coarse and applied it to the wet two-part paint using a plastic peanut butter jar with a lot of holes drilled in the lid like a large salt shaker. The large grain is a good gripper like we need but can be a little uncomfortable when kneeling down with bare knees. Cosmetically, I think the medium grain would be nicer and may not retain discoloration and dirt like the coarse does.

|

|

Applying Propspeed to the Zytel blades of Brick House’s Kiwiprop to improve the ability to resist fouling. |

Going with titanium

Years ago, we changed all our stainless steel chain plates to grade 5 titanium. The price of titanium parts is slowly falling, so we decided this would be the time to replace the 41-year-old stainless steel bow roller/chain plate assembly with one made of titanium. We removed the existing assembly and sent it to Allied Titanium, now located in Sequim, Wash. Grade 5 titanium weighs a little more than half of 316 stainless steel, yet it is over three times stronger. It is not affected by salt water or electrolysis. Since we will be keeping Brick House for a very long time, titanium upgrades and the safety margin this brings us make it a good investment.

While hauled out of the water to paint the bottom in Malaysia, I installed a new fairing block and sonar transducer. This is a new addition to our array of Raymarine navigational electronics. We now have on our big MFD (multifunction display) a sonar that gives a color rendition of what is below our keel down to 900 feet, whether it is rocks or alive and swimming. There is another mode called DownVision, which uses a sweep of frequencies rather than the standard 200 or 50 kHz. This gives far greater detail and definition to the targets. With this viewing equipment, we can see what the textures and contours the ocean floor below us is made of. This is especially useful when feeling our way into remote anchorages and knowing if we make a mistake whether we will be on rocks or soft mud, or how many and how big the fish are outside our cockpit once we are anchored.

Soon we will be away from marinas — we will need to be energy conscious and our alternative energy sources need to be at their best. We took apart our KISS wind generator and put in new thermostats and bearings and rebalanced the blades. It now runs better than it ever has. We also ultimately determined, with help from “Solar Queen” and sailor Amy at altE, that our 25-plus-year-old solar panels were truly at the end of their life. Her team recommended the Morningstar ProStar MPPT-25 solar controller, along with one new 265-watt solar panel to replace our four small 51-watt panels in the same footprint on top of our hard dodger. Prior to this installation, we were seeing about 20 to 30 amp-hours per sunny day. Now we are easily seeing 60 to 70. The team at altE is passionate about solar power, and they are able to provide astounding results.

For all the work we have just completed on Brick House, we should do just fine getting to Durban, South Africa, and on around to Cape Town, where we begin again on the revolving list of maintenance and repairs.

Patrick and Rebecca never expected to spend more than four years sailing away from Rhode Island. Well into their 10th year, they now see no reason to return home with so many places on the planet to explore. Visit www.whereisbrickhouse.com.