An efficient reliable diesel delivers more than the ability to conquer a calm. It’s a bet you can count on in a tight current strewn pass, it’s your best friend when the anchor starts to drag during a predawn squall. These are just two of the reasons why repowering a sound seaworthy sailboat can be one of the best upgrades an owner can make. In short, a new diesel is like a good insurance policy — it’s there when you need it most.

At first the idea of repowering seems quite straight forward. And if sailboats were like SUVs and the process was little more than a one-for-one identical swap of a new engine for an old one, that would be true. Sadly, this is usually not the case. The limited run, often semi-custom nature, of the sailboat industry impacts the plan for cookie-cutter standardization and lessens uniformity when compared with the automotive industry. Also, when it comes time to repower, the original engine may be obsolete or less desirable than a newer model. So instead of an identical one-for-one engine/drive train replacement, the owner has a range of modifications to consider. Some may be as minor as a slight lead angle change for the throttle and shift cables. Others can be as challenging as the installation of new engine beds or how to mate a prop shaft coupling that doesn’t quite line up with the gearbox flange.

|

|

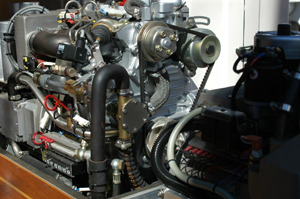

The first question when doing a repower is: Will the replacement engine fit the engine space? This engine must fit inside the engine box. |

At first this mechanical tabula rasa may seem ideal — a chance to re-engineer the engine room, increase or even decrease available horsepower — in essence a chance to cure the ills of a less than perfect predecessor. This is indeed what can be done, but one must keep in mind that the more modifications that need to be accomplished, the more time and money will be spent. Little things like too little clearance beneath a galley counter, lack of space low in the bilge to locate a water trap muffler or other departure from the original engine’s height or width measurements will add complexity to the installation process.

I recall a fellow who towed his sloop to a boatyard I was running. He had responded to an ad that promoted a diesel that fit exactly onto the mount pattern of an Atomic 4 gasoline engine. He bought the engine, ceremoniously gave a Viking farewell to his old quirky gas auxiliary and quickly discovered that the diesel did fit the mounts, but that’s about all that fit. The oil pan was too deep, the valve cover too high and the exhaust system wanted to lay claim to the quarter berth. His perception of a simple, bargain-priced engine swap turned into a pricey carpentry project, not to mention the time and materials linked to the replacement of a hard to get at bottom feed gas tank, and a difficult to engineer exhaust alternative.

Identical replacement

At the end of the day, the installation cost much more than the diesel itself. The bottom line is that an identical replacement cuts down on installation costs and it’s the reason that many mechanics and experienced do-it-yourselfers end up committing to a major overhaul or install a rebuilt engine identical to what was originally aboard in the first place.

However, if your goal is to add more horsepower or abandon an engine that never fit your needs in the first place, the engineering you do up front will pay off in the long run. This process is not a review of the thermodynamics behind internal combustions, it’s more of a plot-plan review that takes into consideration the geometry of the new power plant and its operational requirements. It also involves ancillary issues such as how a larger diameter exhaust hose and bigger muffler might be handled (backpressure caused by too small an exhaust system can degrade the performance and shorten the life of a new diesel).

|

|

The new engine here must fit under the floorboards. |

A tactic I’ve put to good use over the years involves making a crude full-scale, quarter-inch plywood mockup of a proposed new engine that includes all the major dimensions. The exact location of the engine mounts, bottom of the oil pan, and max height and width are accurately portrayed. Even the shaft down angle and coupling at the gearbox are faithfully reproduced. This simple jig can be made from the dimensions found on line or in the engine specs in a manufacturer’s brochure.

Start by making some simple paper patters, transfer these cross sections to plywood and cut out the mockup. Use one-by-two-inch pieces of soft wood to separate and appropriately space these cross sections, (nail, glue or screw the jig together) and viola you have an engine mockup complete with the engine mount location and faux drive shaft (a broom stick stub). This crude full-scale replica will allow the installer to get a pretty accurate feel for what modifications must take place in order to fit the engine being considered. Knowing what challenges lie ahead before buying an engine is a big plus.

Drive train decisions

Even if there’s plenty of space in the engine room/engine space, some important repowering decisions must be made. One of your first considerations is whether or not to stick with a conventional drive system, abandon a much maligned V-drive or make a big switch to a sail drive. The latter’s plusses include the elimination of alignment woes, a smooth as butter shifting process and a plop-in-place installation once the glass work has been accomplished. However, the installation of the latter needs to be done with full recognition that A+ fiberglass work is part of the process. It’s vital to close up the big hole cut in the boat and create a stable engine mount to hull bond. Not only must the secondary bond endure hours of thrust derived cycle loading, but it must also be able to handle the chance encounter with a sizable piece of flotsam. The impact from a submerged timber the size of a telephone pole can take a serious swipe at a protruding sail drive. And while the thought of such blunt trauma torment to the drive leg gets a sailor’s attention, it’s usually the slow fizz of electrolysis that ends up being the sail drive’s biggest enemy. At this point, the verdict is out as to whether the traditional drive train/conventional stuffing box advocates or sail-drive and pod-minded joystick wigglers have the upper hand.

|

|

Installing a new saildrive unit could involve fiberglass work to properly match it to the hull. Another consideration is that ventilating a small engine box often requires an electrical blower. |

What is clear is that the less complicated your engine and drive train happens to be, the more likely you can fix what breaks with a minimum of external support. Mechanical simplicity still equates with reliability for those who voyage far afield.

Most sailboat designers are anything but heroes in the minds of mechanics worldwide. And this wrench-turner antipathy has evolved from a trend that relegates the sailboat auxiliary to a cramped confine that stretches the meaning of “engine room.” Too many mechanical propulsion systems are confined to coffin-like enclosures and the surrounding joinery/molded box does its best to smother the internal combustion process and stifle heat dissipation. Add to this injustice, a mechanical makeover aimed at adding more horses to the cramped coral, and you can see why some engineering intervention is essential.

For example, unless there are sizable funnel vents naturally ventilating the engine room, the addition of an active blower system makes sense. This blower upgrade will help deliver enough air to make a turbo happy or cause a naturally aspirated diesel to run cleaner. It also lengthens the life of the alternator(s) by increasing the availability of cool air that can be vectored by fast-spinning fan blades. Be sure that the blower chosen is a continuous duty model. In many cases, the manufacturer of your new engine will specify the engine room blower needed.

Estimating cost

Before making a commitment to repowering, most sailboat owners want a pretty accurate answer to the question of what it will cost. And the clientele shakes out into three general categories, do-it-yourselfers (DIY), do-it-for-me (DIFM) advocates and a mid-ground cadre that hire a pro for some aspects of the job, but also invest lots of their own sweat equity into the project.

|

|

Good access to pumps, belts, filters, alternator(s), the transmission and the stuffing box is important when undertaking a vessel repowering. |

Working out a repowering budget is a mini-version of what you went through when you bought the boat in the first place. The overall goal is to figure out the “all up cost” ahead of time. This bottom line number includes the price of the engine, ancillary components like a new fuel tank, shaft and cutlass bearing as well as the instrument panel and exhaust system modifications, along with the cost of the labor. Just for the fun of it, also tally the number of hours you intend to commit to the endeavor, the latter often being the most humbling when revisited after all is said and done.

Those in search of a turnkey soup-to-nuts solution still need to develop an understanding of what’s included in repowering and what’s not. And when comparing quotes, small line items such as modifying an existing fuel tank versus replacing the fuel tank, may introduce a four-digit difference in a quote. When deciding upon the right yard or shop to do the work, make sure apples are being compared with apples, and the best way to do that is to develop a detailed spec sheet outlining what you want included in the repowering project. Speak with other sailors who have used the yard or shop and get a look at their work. In the end, picking the right mechanic should be more than a price point decision.

Choosing a new engine

The right size, when it comes to available horsepower, has a lot to do with the performance expectations of the owner. Those who see the engine as a tool for getting into and out of a slip and a reliable means of modest (3/4ths hull speed) progress in a dead calm, usually can get away harnessing a few less horses than most boatbuilders deliver in today’s production boats. Those looking to power up-wind in a seaway, or seek the ability to hit hull speed and then some when the boat is in full trim displacement and towing a dinghy, will double the horsepower harnessed by the prior user. With turbos and inter-cooling options available, the same size engine can satisfy either extreme. For example, in the two-liter size range Yanmar offers the 4JH4 series of engines that ranges from 55 hp to 110 hp — all using the same block and displacement.

|

|

Make sure that the alternator brackets for the new engine afford a rigid mount and don’t flex when under load. |

Some years back, I was pinned downed in Nova Scotia by the remnants of Hurricane Bertha, and from a rain-drenched port I watched two 40-foot sloops caught in a bad anchorage. Waves began to break over their decks, and both boats attempted to clear the anchorage. One of the boats, originally equipped with a 40-hp Perkins diesel, had been repowered with a turbo version of the four-cylinder Yanmar (76 hp). The extra punch derived from the more powerful diesel allowed the sloop to eek its way to safety while the yawl, with her original 40-hp engine, couldn’t make way in the maelstrom and had to remain pinned down awaiting a tow.

In many cases it makes sense to have some power to spare. Going with extra horses and a turbo option usually requires a larger diameter exhaust system and more fuel will be guzzled when the throttle is shoved forward. But when matching the speed delivered by a lower horsepower diesel the fuel consumption is about the same. The bottom line is a 10 percent increase in weight can add a 50 percent or greater boost in power.

Small turbos and naturally-aspirated diesel engines have a great track record, in part thanks to their use in commercial and industrial applications. This, along with growing acceptance as an automotive power plant in compact cars around the world, has helped to refine the two-liter engine. Sailors benefit from the huge R&D and large scale production of these engines. Yanmar, Volvo, Westerbeke, Beta and others marinize these blocks, replacing radiators with raw water pump-fed heat exchangers, marine gearboxes and drive trains leading to propellers rather than radial tires. The quality and reliability of these diesel engines is very good, but the big variable, when it comes to years of unerring performance, is the quality of the installation itself.

————–

Ralph Naranjo is a marine writer and photographer based in Annapolis, Md. Naranjo is also a U.S. Sailing Master Trainer, part of U.S. Sailing’s National Faculty and a past chairman of its Safety at Sea Committee. He is the author of the books Wind Shadow West and Boatyards and Marinas.