Aboard our Dufour ketch Terrapin, we use Navionics on our Raymarine chartplotter and also have two Android tablets with the Navionics app as well as OpenCPN with Google Earth charts. We have found the updated Navionics charts to be very accurate almost all of the time. We still try not to trust them too much. Even if your charts are 99 percent accurate, you are bound to find that 1 percent someday if you put enough miles under your keel.

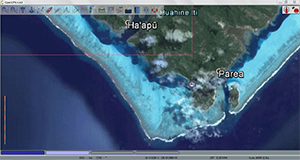

This past June, for example, my family and I were sailing from Mo’orea to Huahine in light winds and fair weather. I had set our course to keep us about two miles off of the reef that surrounds the southeast side of the island. As we made our daylight approach, I noticed breakers that appeared to be much closer than my two-mile comfort zone. I changed course to keep us a safe distance out. When I looked at my chartplotter later, I noticed a slight difference in the location of the reef between zoom levels. The outer zoom showed the edge of the reef slightly east of its actual location. This error resolved itself when the chartplotter was zoomed in to the lower level, and when I compared the location of the edge of the reef at this level to Google Earth charts it was spot-on. I was satisfied that this slight difference in the charts was the reason that the reef appeared closer and didn’t give it much more thought.

Not even two weeks later, we were anchored at the south end of Huahine when we heard a mayday call come through on channel 16 just after sunset. The catamaran Tanda Malaika had hit the reef at the south end of the island less than one mile from our location. Two other cruisers and I got in our dinghies and made a careful approach to the location of the wreck from the inside of the reef to offer assistance to the family of six. Surprisingly, we were able to get our dinghies within 100 yards of the 46-foot Leopard.

|

|

The location of Tanda Malaika at the southern end of the island. |

From there we could see that the surf had pushed the big cat well onto the reef and close to the edge of the lagoon. We were able to wade through waist-deep water the rest of the way to the boat, using its lee to protect us from the huge surf. We made contact with the captain and offered to take the younger crew off the boat. He informed us that a rescue helicopter was en route and they did not want to traverse the reef. We then watched from 100 yards away as the French coast guard helicopter deployed their rescue swimmer, who pulled each of the six family members off the deck of Tanda Malaika. During the next few days, we helped the family get their personal items off and defuel the boat. We were also able to hear from them how the events leading up to the wreck unfolded.

According to the captain, Dan Gavotos, he was on watch and the rest of the crew was down below preparing for dinner. It was just after sunset and as they approached the south side of Huahine, Dan noticed that his depth gauge flashed 180 feet and then zero. He turned hard to port, but the boat was already caught in the surf and slammed into the reef. Dan and the crew claimed the reef was not on their Navionics charts at the zoom level that he was viewing and went on to claim on his blog that they had hit an “uncharted” reef. This claim prompted Navionics to issue a statement on their website reminding mariners that “electronic charts are not 100 percent accurate and never to rely on any single form of navigation.”

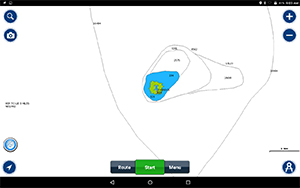

Just over a month later, the catamaran Avanti was lost on Beveridge Reef while en route to Niue. According to the captain, Bobby Cooper, the chartplotter was zoomed out to 100 miles and did not show the reef. It wasn’t until he zoomed in to the 18-mile level that the reef appeared. Fortunately, a research vessel was anchored inside the reef and was able to rescue the family of four.

|

|

|

The satellite image view (top) compared to the chart view of the Huahine reef. |

Both of these cases drew their fair share of criticism from the sailing community, and deservedly so. In the case of Tanda Malaika, their boat was lost on the reef that surrounds the island of Huahine. Even if the location of the reef is not accurate, a wide berth should be given to the island, especially when approaching at night. The claim that they hit an “uncharted” reef cannot therefore be substantiated. Similarly, Avanti hit Beveridge Reef, which is a well-known stop between Palmerston Atoll and the island nation of Niue. Our Navionics chart does show Beveridge Reef at the outer zoom levels, although it is unclear at this level whether or not this is a reef or just shallow water. However, prudent and thorough passage planning would have shown this to be an obstacle along the proposed route.

Since these two events took place earlier this year, we have heard at least a dozen or more stories of major and minor accidents as well as near misses attributed to discrepancies or “zoom errors” in electronic charts. Indeed, as I am writing this article, some of our friends reported rudder damage after hitting a reef just outside Musket Cove in Fiji. In this case, our friend claimed that the reef was not shown until his Navionics chartplotter was zoomed in to 500 feet! Two other boats sustained heavy damage from grounding while traversing the north side of Viti Levu, an area notorious for its gauntlet of reefs. Both of these boats also reported discrepancies in zoom levels.

Electronic navigation has provided a means for sailors with minimal navigational experience to access the planet using GPS and electronic charts. It is exceedingly rare these days to come across a sailor with celestial navigation experience. The ease of use, accuracy and availability of chartplotters and navigation apps have made bluewater cruising more accessible and, arguably, safer as well. As the use of these products becomes widespread and commonplace, however, reliance on them as a sole means of navigation and complacency become more of a danger as the previous examples show.

It is important to remember that these products are merely tools and even the most precise tools require a skilled user with common sense and discretion. We have found that the combination of these tools along with careful passage planning and a vigilant watch result in safer, less stressful passages. Here are a few tips from what we have learned navigating the Pacific using electronic charts.

Be redundant

Redundancy on a boat is always a good thing. Most skippers would not even consider an ocean passage without the full gamut of spare sails, halyards, engine parts, autopilots and everything else one can imagine to anticipate all of the breakages that are bound to occur while sailing across thousands of miles of open water. Just a few years ago, carrying a spare chartplotter and GPS receiver could be prohibitively expensive. Navigation apps for tablets and phones have recently made redundancy for electronic chartplotters easier and much cheaper.

|

|

|

Two views of Beveridge Reef on Navionics charts. At top, zoomed out and above, zoomed in. |

We use Lenovo tablets with integrated GPS purchased on Amazon for about $100 each as our backups. The advantage of using tablets is their portability, minimal power consumption and the low cost of these units, which allows us to have multiple backups on board. In addition, we can run different navigation apps on a single device. For example, we use Navionics and OpenCPN in tandem on our tablets. OpenCPN is a free navigation app available for Android that can reference multiple types of charts including Google Earth KAP charts. Google Earth charts are created from actual satellite images, making them excellent backups due to their accuracy. We often check the accuracy of our Navionics charts by comparing positions and waypoints in OpenCPN. Versions of these charts for different areas are frequently passed around by cruisers and new charts can be easily created for just about anywhere on the planet with a simple program called GE2KAP. For more information on using OpenCPN with Google Earth charts, go to opencpn.org and www.gdayii.ca.

Be up to date

Nautical charts are constantly being updated and improved as old surveys are replaced with accurate satellite-based surveys. When we sailed to Mexico in 2015, we had the pre-2008 Navionics chip in our chartplotter. We found these charts to be extremely unreliable and, in some cases, up to two miles off! We promptly upgraded to the newer version with updated surveys and found these to be very accurate in most cases. Most navigation apps and newer chartplotters can be easily updated in minutes with an Internet connection. Every time we are in port, we update our Navionics charts before heading out again.

For app users, it is also important to make sure that that the operating system on the device is up to date as well, especially if the device is an Apple product. We have heard of several cases where iPads and iPhones will stop working completely until the updated OS can be downloaded and installed. Just this year, a sailor called in on the Magellan Net to request assistance when his iPad, the only form of navigation on board, stopped working when an update was required. He was en route from French Polynesia to the Cook Islands and reached his destination by using a hand-held GPS to get heading and range.

Be low-tech

The above example also illustrates how dependency solely on electronics can be potentially dangerous. Had the skipper carried paper charts, he would have easily been able to plot his way to his destination. Before our Pacific crossing, we made large-format copies of as many charts as we could get our hands on. All of these charts are available should our chartplotters go offline.

A glaring dependency of all of these systems is the GPS satellite network. If this system were to ever go offline, most sailors would be in big trouble. The ability to plot position, determine heading and course, dead reckon and triangulate position are absolutely essential skills to have. Additionally, it is important to log position, speed and course after every watch should GPS become unavailable. A sailor with the ability to navigate with a sextant is indeed rare these days, but these few are the only true navigators who are fully independent from electronics and GPS.

Be aware

Navigation should be an active process that involves planning and constant vigilance. Charts should be examined ahead of time to identify any hazards, discrepancies or other important details along your route. Be sure to look at different zoom levels along the route to reveal any potentially hidden details or “zoom errors.”

|

|

A bow watch is a great idea when operating the vicinity of coral. |

|

Phil Nance |

All of this should be done not only before but also during passage. It is all too easy and common, especially during an ocean passage, to get caught up in reading, watching movies or other activities to pass the time while on watch. One of the most common and preventable mistakes that sailors make both offshore and inshore is not paying attention to their surroundings. The best navigational tool available is a pair of eyes. Look up and look often. Be aware of your environment and trust your eyes.

If something doesn’t look right, go with what you see in front of you over what your charts may show. In an area with reefs or other hazards, put someone on the bow as a lookout. Two sets of eyes are always better than one. More than once, my wife and first mate Aimee has saved me from making a bone-headed mistake. A fresh perspective could be the difference between a safe arrival and disaster.

Phil Nance has been cruising the waters of the Pacific with his family aboard their 1978 Dufour ketch Terrapin for three years. They are currently in Savusavu, Fiji, for cyclone season. Visit www.sailingwithterrapin.com.