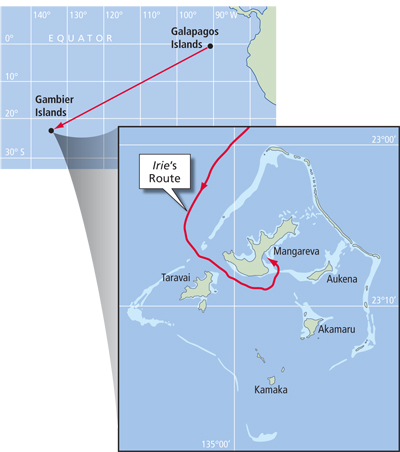

My husband Mark and I were aboard our 35-foot Fountaine Pajot Tobago cat Irie on a passage from Isabela Island in the Galapagos to Mangareva in the Gambier Islands. We were making our first cruising foray into the South Pacific.

The waves had been coming from three directions on our side, topped with tumultuous chop from the strong winds. They collided underneath Irie, creating terrifying sounds and abrupt movements. Our boat was constantly swinging, pitching, bucking and banging into the waves. She swayed from left to right, lifted up, went back down. Luckily not all the way down. Being lifted up and then landing with a smack and a crash back onto the water made napping — made anything — impossible. The hulls whizzed through the water next to our sleepy heads. The waves were explosives: crack, bang, kaboom! Once in a while there was a huge one. It sent a shiver throughout our house and our bodies; our whole home vibrated and flexed.

An unexpected jerk followed by a thunderous boom flashed me back to reality.

|

|

The passage between the Galapagos and the Gambier islands was marked by storms and high seas. |

“What the hell was that?” I screamed, simultaneously jumping up. I set my queasiness aside and checked our saloon. Several objects were spread over the floor — this was not allowed on our catamaran! Stuff on the shelves ought to stay on the shelves. I crawled over the ground, bracing myself against anything that wasn’t wobbly, snatching the books, utensils and souvenirs scattered on the floor. By the time I finished cleaning up, my face was green and I was in urgent need of fresh air. I spewed the contents of my stomach into the turbulent ocean.

The 30-knot southeasterly steadily grew to 35 knots, gusting stronger and stronger. The sea grew exponentially. Waves the size of a two-story building joined us, fueled by frequent squalls. They picked up Irie and tossed her about like she was a plastic toy thrown around a bathtub by a frustrated toddler. We both remained in the cockpit at all times, hooked on for safety.

“Look at that wave.” My gaze froze as I saw a foaming mass of water approach. “Quick, close the hatch!”

It was too late. Seawater flooded the cockpit and made its way into the saloon. I bounced back into the cabin to clean up the salty mess. After my efforts, I was sick again and rushed back out on deck. As I could tell from up close, Irie was flying along at 7 to 8 knots. She was performing beautifully, speedwise: We were covering around 170 miles every 24 hours. It was a hell of a ride, but she was on top of it.

|

|

Liesbet and Mark in the South Pacific. |

At a snail’s pace

I missed the early days of this crossing when we progressed at a snail’s pace and wondered whether we’d ever get there. The water is always bluer on the other side. At least the sea had been calm. We could bake bread and occupy ourselves in a pleasant way. Those days were over — our world had been turned upside down without an end in sight. Another crashing wall of water soaked everything and everyone in our cockpit: table, seats, cushions, stack of bananas, plants, geckos and us. Water leaked into the head through the solar vent. The sealant needed replacing, but it wasn’t the time to battle such a project. We duct-taped a plastic salad bowl upside down over the vent. Problem solved.

Beep, beep, beep. Now what? One of the water alarms had gone off. It was Mark’s turn to enter Irie’s bowels, while I intently stared at the wavy horizon. Seawater had entered the port engine room through the air vent and hose. One of the waves must have hit the miniature opening under the “Fountaine Pajot Tobago” plaque just right. More cleaning up with cloths, sponges and fresh water caused the customary bruises. Our tired brains were put to the test: How could we avoid this influx of water, and particularly the cleanup, in the future? I wobbled down to join Mark down below. We took the thick, plastic air hose off and stuffed the hole in the hull with a towel. Our collective IQ was fried and dwindling. Not an hour later, a giant wave pushed the towel back and dumped gallons of seawater into our engine room. We mopped and rinsed and dabbed fresh water wherever we could reach. We put the hose back. Then, I puked again.

|

|

Flying fish and squid on the deck of Irie. |

“Are you still having fun?” My husband rubbed it in. No, this sucks. But it’s the only way to reach the islands. Only seven more days of this, or 10, or 15. And so it went. Day after day. Hour after hour. Like zombies, we sat in the cockpit, we checked the instruments, we adjusted the sails, we tried to nap, we dealt with unexpected issues and surprises, and we complained until even that required too much effort. The month of May was progressing slowly and intently. It’s OK, I could handle it. As long as Mark, Irie and I eventually got there without losing our sanity — or more.

A settled sea

Everything ends, even uncomfortable times at sea. On day 15 of our Pacific crossing, the wind and waves settled down, and we returned to pre-hellish conditions. The weather cooperated again; I didn’t have to fight seasickness, water intrusion and discomfort anymore. Mark made a delectable oversized pumpkin soup with 3 pounds of fresh pumpkin and three carrots thrown in. We prepared favorite dishes, like falafel on homemade spinach flatbread, spaghetti carbonara, shrimp curry, exquisite salads with eggs, cheese, ham and beets, and American-Belgian chocolate-chip cookies.

Mark and I aren’t the kind of people who like routines. But on this trip, we had somewhat of a schedule. During daylight, we were both up and on deck, and at night we stuck to six hours off and six hours on watch. That may seem like a long time to be awake in the dark (it is), but I liked it — when the sea was behaving, that is. It allowed a big chunk of “me time”; I could do whatever I pleased in the cockpit, within the realm of an ever-moving surface the size of a bathroom. The sky exploded with bright stars. Our trail sparkled with phosphorescence. I kept an eye on the instruments and the sails. Every 15 minutes, I stood up and checked the horizon in case there was an obstacle on our path.

|

|

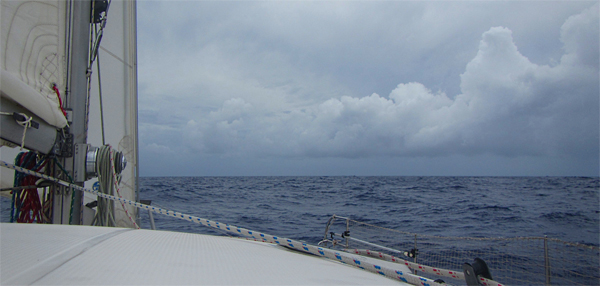

On approaching Mangareva, Irie was swept by one final storm. |

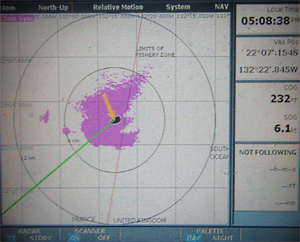

When something was amiss or appeared unusual — an approaching light on the horizon, a blotch closing in on the radar, a substantial shift in the wind, an imminent storm or an alarming sound — I woke Mark up. It was our most important rule after “Do not fall overboard,” which is paired with “Always wear your life jacket and stay attached to the boat.” They were Irie’s “Rules of the Night” and could mean the difference between life and death. Our duty to alarm each other when we thought necessary was the key to sleeping without worries, a restful six hours in ideal circumstances. That was the advantage of a long night shift.

Every five days, we took a full-fledged shower. Because it was too dangerous to dunk ourselves into the ocean, even with a line attached to the boat, we came up with a different system. Our primary sun shower contained fresh water from the island of Isabela, and our broken “spare” sun shower with its leaking cap and loose hose was filled with seawater by a bucket. There’s a lot of force and resistance from the water when you’re gliding, or bouncing, along at 6.5 knots. Caution has to be taken so that neither bucket nor person is lost overboard. After allowing the water to warm up on deck, the salt water part of the routine consisted of wetting, washing with shampoo and rinsing. The second part was the familiar rinse-off with fresh water out of the primary sun shower. Losing our balance umpteen times was part of the experience.

|

|

In the midst of squally weather. |

Mark and I only had one fresh water tank that held 53 gallons (200 liters) of water. We also carried four six-gallon jerrycans, of which two were filled for this crossing. We couldn’t make the boat any heavier and didn’t have room to store four full jugs. This added 12 gallons (45 liters) of water to our supply, which we kept for the main sun shower and emergencies. At anchor, those 65 gallons lasted us about one month. We used our filtered tank water to wash up, brush our teeth, rinse the dishes, cook and drink. We learned to become prudent with fresh water, utilizing seawater wherever possible. This habit comes in handy on passages that might last more than one month.

The seas had subsided and the ride was slow, yet more comfortable. We’d get there after all. The new weather brought light winds that were inconsistent. The wind meter’s needle bounced around between southeast and northeast, and so did we, constantly changing course and adjusting the sails. It was a tiring job. When the wind picked up again, we saw stormy weather on the horizon. We fought it head-on for two days.

|

|

The radar screen shows Irie being hit by a squall. |

Approaching landfall

Before making landfall in the South Seas, after a multiple-week odyssey, a popular and often-advertised image came to mind: lush mountains, pristine white-sand beaches, turquoise water, a bright blue sky. Local beauties await with baskets of tropical fruits and fragrant flowers in their long black hair. The crossing and its challenges were finally over. I could smell dirt. We were almost there. Land ho! A vague contour line was visible in the distance — or were those clouds? Twenty pencil marks decorated the fiberglass wall in the cockpit, one for each day. We were ready to arrive in Rikitea town. I could taste the sweet fruit it had in abundance. I wondered who would be there. I couldn’t wait to catch up with everyone, to be able to walk on land again, to sleep in a stable bed.

My daydreaming didn’t last long; reality hit with a thunderclap and a giant gush. As the fantasized land approached, it turned black and morphed into another full-blown storm. I struggled to write a daily update for “It’s Irie,” my blog to keep family and friends abreast of our progress. I couldn’t get further than: “Too rough. Too uncomfortable. Too wet. Too bouncy. Too seasick. Too exhausted. Too much wind, 25 to 30 knots on the nose! Too frustrating … to write a full-size blog. 68 more annoying miles to go. Almost there. Almost!”

After a sleepless night, I put the 21st pencil mark above our sliding door. Will this be the last one? Where is the island? Mangareva’s mountaintops appeared and disappeared again, shrouded by clouds and rain. A few hours of consistent wind and progress were followed by the most dreadful weather. The low-pressure system we hoped to avoid was coming right at us. We doused the jib, ran the engines at full power and bashed into the waves, wind chop and an outgoing current to approach the safety of the lagoon. We crept forward at 3 knots. Heavy rain drove into our faces and salty waves crashed over the bows. Our boat was struggling. The worst was kept for last.

|

|

A rainbow above the anchorage at Rikitea. |

Mark and I navigated the inexhaustible Irie through the wide entrance into the Gambier ring of islands. Instead of azure blue, the water was lead gray. Despite being in protected waters, the heavy frontal wind created short, steep waves. We needed to dive into them and bounce our way toward the harbor. We remained in the channel, bows pointed into wind and waves. It took four hours to cover the last 10 miles.

Approaching the anchorage of Rikitea, drenched and utterly exhausted, we were welcomed with cheering, ringing bells and foghorns. Goosebumps erupted on my arms. Tears welled up. We made it. Everywhere we looked, fellow cruisers waved us on and screamed compliments across the water. They acknowledged Irie’s accomplishment: Our small boat had achieved a big feat. They knew what we had gone through. Once we were settled, our friends Birgit and Christian from SV Pitufa came by to say hello and handed us a basket full of local produce, a fresh baguette and a bottle of bubbles. She had a tiare flower in her hair.

Liesbet Collaert is a freelance writer, photographer and translator now writing a memoir of her sailing adventures.

|

|

One of the rare sunrises at sea that the Irie crew experienced on their passage to the Gambier Islands. |