An accident at sea is a much larger event than a similar accident ashore. Distance from medical care, lack of ambulance service, and cold, wet, cramped and uncomfortable conditions aboard a vessel at sea in a blow — these complicate even the simplest of injuries or illness. How can we manage that risk, and what can we do to save a shipmate or ourselves?

Preparation

Prior to tossing the dock lines, each of us needs a full medical and dental work-up. This can be done by a family doctor, or a medical team (WorldClinic) that is prepared to respond electronically should medical assistance be needed while you are underway.

Keep your medical records with you, as a digital file as well as a hard copy. When you reach a shoreside medical facility, the medical team there will be better prepared to provide the proper assistance with your records in hand.

Your doctor, knowing you, can better suggest a list of medications (over-the-counter and prescription) to take with you. They can help you tailor your shipboard medical kit, stowed in a watertight case so it can go aboard the life raft. A few of the organizations listed here can tailor your medical first-aid kit, reflecting your crew’s potential medical needs.

|

|

Divers Alert Network (DAN) recently announced a dedicated DAN for Boaters service. |

When signing on crew for your next voyage, have them provide you with a medical resume. You need to know what medications they take, and if they have any allergies or aversions to medication. You also need to know if they have any medical conditions, who their personal physician is and their contact information.

Education

Learn how to take care of yourself and your crew in an emergency. This may require enrolling in specific courses in offshore medicine. A local CPR course is your first step, but not your last. A few wilderness and marine organizations provide courses in basic triage, treatment for shock, cleaning and suturing wounds, applying a splint, treating burns, hypothermia, even toothaches. These courses provide you with enough knowledge to stabilize a patient and prepare them for evacuation, and the long trip to shore.

Ocean Navigator has been conducting a three-day offshore emergency medicine course for the past 17 years, in conjunction with Wilderness and Rescue Medicine of Crested Butte, Colorado. You can find more info at www.medofficer.net.

|

|

An Iridium satphone for worldwide communications. |

|

Courtesy Iridium |

Stabilization

Your first action following a traumatic injury on board is to stabilize the boat and the rest of the crew. Once that key task is quickly handled, then you need to stabilize the patient. Learning how to treat for shock, stop bleeding, restore breathing and hydrate a patient will go a long way to your patient’s survival. With the patient comfortable and secure below, there is time for more investigation. Record vital signs, as they will tell you a lot about the patient’s condition, and this information will be requested should you take the next logical step: calling for outside help.

Communication

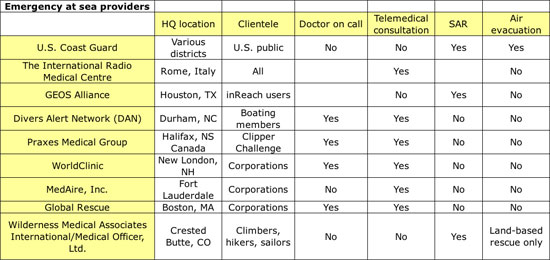

When the situation is beyond your knowledge and skill, it’s time to call for help. This is generally not the Coast Guard — your call will be to a telemedical organization, which can provide a greater level of advice on the patient’s stabilization, medication and first aid. These calls can be made via shortwave radio (SSB), satphone, email or text (see table at bottom). Telemedical organizations are designed to handle medical emergencies in remote locations and advise on medications or even basic surgical procedures. But, as Jeffrey Isaac, a medical emergency authority, relates: “Advice from afar is just one of the tools you may need to help you manage your patient. Beware of any service or device that purports to be all that you need to handle any medical emergency.” Your knowledge, experience and a cool head in a crisis will be your best tool.

Consultation

There are numerous telemedical clinics that can provide long-distance medical advice. Voyagers need to consider the options and pick a service that is right for you (see accompanying table of providers).

|

|

Global Rescue is a medical assistance firm based in Boston, Mass. |

DAN, the Divers Alert Network, has been providing recreational and commercial hard-hat divers with emergency assistance since 1985. The recently announced DAN for Boaters provides surgical advice by an on-staff medical team via satphone, email and text messages. For a $60-per-year membership ($100 for a family), DAN for Boaters will provide remote consultation and, once the patient is ashore, they will arrange for medical care and expedited travel to a convenient medical facility — even taking them all the way home — for up to $100,000 reimbursable expenses. A recent issue of Ocean Navigator included a story about how DAN helped one of its members fly from the Solomon Islands to Australia to get treatment for a heart attack (“Emergency in the Solomons,” October 2014).

Doctor Dan Carlin’s team at WorldClinic has been providing medical support and advising sailors on medical procedures and stabilization in mid-ocean since 1998, when he talked a Russian solo sailor in the South Atlantic through a procedure on his own infected elbow — via emails. WorldClinic now provides pre-departure medical exams, tailored medical kits, and 24/7 medical advice to its clients.

Praxes Medical Group in Halifax, Nova Scotia, has a team of emergency room doctors available to consult with vessels at sea (they work with the Clipper Challenge Race), remote oil rigs and mining operations north of the Arctic Circle.

Telemedical services are not walk-in clinics. They require an upfront, paid membership — think AAA for mariners. A few are set up specifically to assist executives of international corporations working in potentially dangerous countries, and passengers and crew on megayachts and cruise ships. These “personalized” services are costly, but there are more cost-effective options for the family or couple cruising the world on their yacht. Keep in mind, these organizations do not replace the hospital emergency ward or cover a hospitalization; your own medical or health insurance plan does that.

|

|

GEOS operates an International Emergency Response Coordination Center in Houston. |

Evacuation

Once the injured crewmember or sick patient is stabilized and resting comfortably, it’s time to consider evacuation to a shore-based medical facility.

Jeff Isaac advises: “If your crewmember is stabilized and resting comfortably, why evacuate? A telemedicine service can help you decide if evacuation is medically necessary. The captain, of course, will have to make the final decision based on advice from medical personnel, weather and sea conditions, and available rescue resources. Many times the risk/benefit ratio will favor keeping the injured or ill crewmember aboard. Again, a telemedicine service can help you manage your patient during the hours or days it may take to reach port safely.”

If evacuation is advised, what are your options? If within 200 nm of shore and if conditions warrant, evacuation by U.S. Coast Guard helicopter is possible. If further out, it’s on a case-by-case basis. The Coast Guard can also request commercial shipping to divert and assist when rescue by helicopter is not possible (most ships participate in the AMVER program). The Coast Guard listens in on VHF frequency 16, or on multiple shortwave channels (see www.navcen.uscg.gov/?pageName=mtHighFrequency). Or, if you have no other way to reach them, you can call them on your satphone or cellphone. The district numbers are available on their website. They do not accept emails. The Coast Guard has a new a smartphone app with an “emergency assistance” button.

Other than the U.S. Coast Guard, there are few organizations that will arrange for an “extraction” from your boat. Some of the shore-based emergency organizations, like Global Rescue and MedAire, will coordinate travel all the way home once the patient is ashore. Medical treatment along the way is to be covered by the patient’s own medical insurance plan.

|

|