The first thing I ordered when I purchased my boat were two log books: a general log and a maintenance log. The general log book is where I record the underway activity of my boat. A short afternoon sail will get one log entry when I return to the dock, but an extended distance sail like a race around an island may get entries every few hours. My maintenance log is where I record all maintenance and repair activity. In the front, I record chronologically the work done and the related cost. This could mean replacing a turnbuckle or having a diver put a new zinc on the propeller shaft. Starting on the last page, I record the engine service dates and what was serviced.

The first thing I ordered when I purchased my boat were two log books: a general log and a maintenance log. The general log book is where I record the underway activity of my boat. A short afternoon sail will get one log entry when I return to the dock, but an extended distance sail like a race around an island may get entries every few hours. My maintenance log is where I record all maintenance and repair activity. In the front, I record chronologically the work done and the related cost. This could mean replacing a turnbuckle or having a diver put a new zinc on the propeller shaft. Starting on the last page, I record the engine service dates and what was serviced.

The origin of a log book goes back centuries to when sailors measured the speed of a vessel using a device called a “chip log” or “common log.” The device was simply a spool of line called the log line, with knots tied into it at established intervals proportional to a nautical mile. A nautical mile is equal to 1.15 imperial miles or one minute of latitude (the horizontal lines drawn around the earth parallel to the equator) at the earth’s equator. A triangular board with a convex bottom side was connected with a bridal at the end of the log line. When thrown overboard, the board would create drag like a sea anchor, and the log line coiled around the spool would be payed out. An hourglass would be used to measure time. The number of knots counted was equal to the speed of the boat. A nautical mile is equal to 1.15 imperial miles or one minute of latitude (the horizontal lines drawn around the earth parallel to the equator) at the earth’s equator. This information would be recorded in a “log book.” Over the years, more information such as the vessel’s course, observations, weather, and significant events began being recorded in the log book.

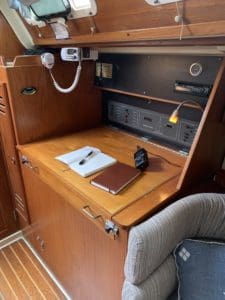

The first captain I worked for was adamant about recording the activities of our boat in a log book kept readily accessible in the chart table. He would make a log entry every time the boat left the dock. Day sails, usually less than eight hours, only required one entry entered after returning to the dock while the crew was washing the boat down and putting the sail covers on. His daily log entry was always written in the same format and order: date, names of the crew and passengers, environmental observations, and a couple of sentences about where we sailed and the events that occurred. Environmental observations included the sea’s state, the wind’s strength, direction, and the weather.

A more comprehensive log entry was entered if we were doing a destination sail or delivery, sailing to a different port for a charter. These longer sails might mean being underway for more than 24 hours and sailing through the night. For these types of sails, our crew was divided in two, so we could alternate the operation of our boat in four-hour watch cycles. When not at the helm, one of the watch responsibilities as a crew member was to conduct an hourly “boat check” and record the observations in the log book. Before retiring for the night, our captain would take the time to explain to each crew member how log entries were to be made. From the hours of 16:00 to 08:00 the following day, log entries were entered on an hourly basis and included:

- Time of entry in 24-hour format.

- The heading being steered and our latitude and longitude.

- Environmental observations: We were directed to include an estimated range of visibility when on deck.

- Engine status: If the engine was running, we would check its temperature and rpm’s, and conduct a visual inspection to confirm nothing out of the ordinary was happening, such as an oil or coolant leak.

- Boat check status, after a walk through the boat’s interior to ensure nothing had come loose and all other crew members were safely asleep.

- Unusual odors, if any, and verification of water-free bilges

- Results of an on-deck inspection of sheets, halyards, and standing rigging to confirm nothing has chafed through and no lines had fallen over the side. We would also shine a flashlight on the sails to check for tears and unusual wear.

- Sail changes and adjustments, any observations of marine traffic, notable landmarks and navigational marks .

The list above may seem excessive, but the routine kept us on our toes. Over the years, my log entry habits have helped me to discover and prevent several potentially terrible situations.

Will Sofrin lives in Los Angeles with his wife and six-year-old daughter. He is a graduate of IYRS School of Technology & Trades, where he apprenticed in the wooden boat restoration program. After completing the program, he spent a decade working as a professional sailor, earning his 100-ton master’s license, and using his specialized wood-working skillset to secure positions on yachts and ships sailing through Europe, New England, the Caribbean, Central America, and the California coast. In 2014 he launched a design firm specializing in managing the restoration of historic homes and developing ground-up architectural packages for luxury residential homes. He still sails actively on his Pearson 33-2, participating in races in Santa Monica Bay as well as a number of double-handed near coastal races.