To the editor: My wife and I had one of those “learning experiences” this summer. We were on a three-week-long trip to the Broughton Archipelago — up towards the north end of Vancouver Island — as a vacation, sure, but also as something of a sea trial for us and for Serafina — our 36-foot Cape George Cutter. We wanted to test the systems we’d updated or replaced last winter, after our purchase of the boat in September 2010.

It was on the way back that our sea-trial got serious. One night we anchored in Gowlland Harbor on Quadra Island, British Columbia. The next morning we raised the anchor to get underway, eased her into gear and heard a loud thumping, from what seemed to be the region of the propeller. “Damn, we’ve got a piece of wood in the prop,” I thought. We reset the anchor and launched the dinghy, but looking through the clear water, everything looked normal. The prop looked fine — free of wood or crab pot lines.

Puzzled, I opened the engine compartment and watched while my wife, Birgit, gently put the engine in gear — and saw the engine hop around, pounding against the hull. Clearly, we had lost a motor mount. The engine only jumped at very low rpm, so when I called the mechanic who had worked on the 20-year-old BMW marine diesel last winter, he and I decided that if we ran the engine at an rpm that didn’t bounce it around, we could limp back home.

After a few nights, we anchored in Deep Bay on Jedediah Island. Our next stop was Nanaimo.

In the morning we lashed down the dinghy and made everything ship-shape for a breezy crossing. About three miles south of Texada Island we were shocked to hear a loud banging coming from the aft end of the boat. The tiller became sluggish to manage. Once again I thought we had picked up a piece of wood in the prop. So I shoved the gearshift into forward to stop the rotation. No change! Still an alarming “Bang, Bang, Bang!” from under the stern. I was baffled.

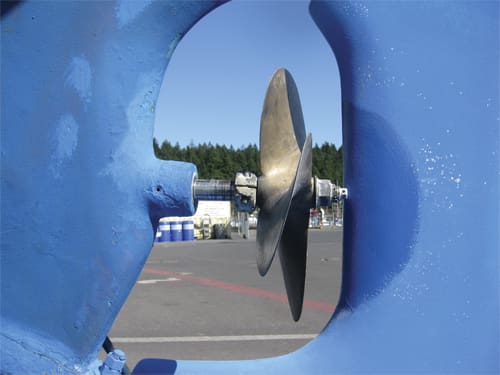

Not being able to think of anything else, I opened the engine compartment and crawled over the engine to look at the shaft. I saw a spinning shaft and coupling, no longer connected to the transmission! It had slid back far enough that the propeller was chewing on the rudder, and that was where the banging was coming from. Perhaps worse, the bolted coupling was doing its best to tear through a couple of large hoses that constitute part of the exhaust system and lead out to sea.

After jamming some wood under the coupling and tying a spider-web of seine twine to immobilize the spinning shaft, quiet returned. We didn’t know how badly the rudder was damaged, or when the propeller might jam it.

I alerted the Canadian Coast Guard that we would be sailing into Nanaimo without power, and that we would like to request a tow once we were in the harbor. The rudder seemed to be working OK. The wind was picking up, maybe 25 knots by now, and it would be a wet and windy beat into Nanaimo, but we would do it. The Coast Guard put out a marine assistance request. It was promptly answered by a towing company which I’ll call “Gump and Company Towing.”

I got a cell phone number for the office of “Gump and Comp.” and spoke to a fellow there who insisted that we sail into Departure Bay, north of Nanaimo. It would take us 10 or 15 degrees farther to windward, in strong wind and four- to six-foot chop, but we saw we could make it and agreed, emphasizing that when we entered Departure Bay we wanted the towing vessel promptly at hand, to hold us into the wind to get sails down and put away. “Gump” was associated with a boatyard, and said they would tow us directly to a marine lift where we would be hauled out. $180 was agreed as the price for the tow. Not bad.

In hindsight, it was a mistake to go into Departure Bay. It’s small and fairly deep, while the main harbor in Nanaimo is relatively shallow, more protected, and it would have been easy to sail in, drop the anchor and arrange for repairs at leisure. We wouldn’t have been at the mercy of the towing crew, who I’ll call Bert and Ernie, and their boss.

I asked what VHF channel we would work on. He said they didn’t have a VHF, and that we would have to stay in touch by cell phone. That should have been a warning, but we had other things on our mind.

We sailed past the rocks at the entrance to Departure Bay at eight knots or more with still no sign of the towing vessel — that is, until we noticed a low, 20-foot (or so) waterskiing boat with some writing on the side. They waved — they were the Gump guys! Inside the bay it was flat but still windy, and we let the sheets go. Since the only cell phone number I had was to their office, we had to shout through their engine noise and the flapping sails to make arrangements for the tow. We had a line ready up forward, but they said they didn’t need it.

They brought out a yellow polypropelene line, backed up to the bowsprit, and one guy threaded it under the bowsprit and around the bobstay. Then, holding the line in his hands, he turned to his buddy and said, “OK, we got ‘em.” Bert put power to the boat, and the line slipped through Ernie’s fingers. “Ow,” he said.

There seemed to be no cleats on the boat, or at least they had trouble finding them when they came back and tried again. Finally they got the line secured and our bow pulled around to the wind. We dropped both sails. The headsail was no problem, but when we started to gather up the main we were surprised to find ourselves sideways to the 25-knot breeze.

“Keep us to (expletive) windward,” I shouted. “Huh?” they replied. I thought they were being stubborn and obtuse, but actually I was wrong. Their sterndrive had failed and wouldn’t go into forward. They were embarrassed by this, and were reluctant to discuss the subject. They opened the engine cover and did some hammering, meanwhile we drifted towards the beach.

I got the anchor ready to go, then I called the “Gump” office. “You need to get another boat out here. Now you’ve got two boats that need a tow!” “OK,” said the boss, who did have a charming Aussie or Kiwi accent.

Meanwhile Bert shouted, “No problem, we’ll tow you in reverse.” This led to an interesting effort by Ernie to climb forward over the ski boat dodger to get to the tiny cleat on the bow. Line got tangled, there seemed to be some question about whether the line should go over or under the dodger, but somehow it got figured out and they held us into the wind long enough to lash the mainsail to the boom.

Then we began our tow, backwards. I noticed out of the corner of my eye an eight- or nine-foot rubber dinghy. It was the second “Gump” vessel! It boasted a five-hp outboard, and also no VHF, but the guy had one of those cool Aussie bush hats pinned up on one side. Just about the time of his arrival, there was a loud “Clunk!” from the ski boat, and they had a forward gear again. They switched the line around to the stern of their boat, and we were in business, in tow with an escort vessel.

There’s a narrow channel between Departure Bay and Nanaimo Harbor, and that’s where we headed. From shouts across the water and above the engine noise, we learned that the strategy was that they would build up speed, and when we got to the marina entrance they would turn us loose and we would steer ourselves into the travel lift, which we could see by now, about 50 yards beyond the sharp right turn into the marina.

“Um, OK,” I said, “but how about some plans for stopping us?” No response, except to take the line off the bow and point in the direction we were to drive. We looked up and saw people on the boat moored at the harbor entrance scramble up on deck with fenders in their hands. Apparently they had experience from previous “Gump and Company” operations.

Once we turned the corner, I could see it was a straight shot into the travel lift, no problem, except for that wall of big rough rocks right on the other side. By now the guy with the cool hat and the 5-hp motor was cruising alongside. “How are we going to stop?” I asked. “Oh, no problem, just drive up against the dock before the travel lift, we’ve got people there.” I looked and saw two young women with boathooks. They looked determined, but the boat weighs 23,300 pounds, and we were moving pretty fast.

Having no choice, I steered towards the dock, and, miraculously, we glided to a gentle stop. “What?” I thought. It seemed like inexplicable events were piling up that afternoon. It wasn’t, though, actually, that inexplicable. We were firmly aground.

A couple of hours later — after the tide had come in — we were lifted out of the water and the repairs began. The boatyard itself was very helpful, and amazingly there was no damage to the prop — it was the nut holding the propeller to the shaft that chewed on the rudder, and the rudder damage was minimal. Meanwhile, it turned out that we didn’t have a broken rubber motor mount, but that one of the aft steel brackets that hold the engine to the motor mounts had snapped. It dropped the engine far enough that the lateral pressure on the coupling unscrewed the nut that held the coupling to the transmission output shaft. It could have been way worse.

Two days later we were back in the water with a repaired bracket, through Dodd Narrows, and on a lovely sail downwind through the Gulf Islands.

——————-

—Syd Stapleton has a 200-ton Master’s license for power, sail and towing. In 1996 he sailed – in a 1935 wooden schooner – from Washington state to the Caribbean (and back).