In 1897 singlehanded circumnavigator Joshua Slocum undertook to sail night and day inside the Great Barrier Reef channel. He had been warned against it. A Royal Navy captain who had done the trip aboard HMS Orlando told him that while such a passage was possible for steamships, it would not be wise for a sailing vessel. Instead, Spray ought to anchor every night. Slocum was not to be persuaded, however. He decided he was finished with the tiring work of getting his sloop underway each morning after he had cleared the Strait of Magellan. Further, he believed that between his admiralty charts and the clear June weather, he could make a continuous passage safely.

The success of Slocum’s voyage inside the reef has not diminished the warnings one hears today when contemplating the same passage. When Seth and I were in Cairns, Australia, readying our 38-foot cutter Heretic for her voyage north, we were cautioned repeatedly that we had to anchor every evening since it wasn’t safe to attempt the minefield of coral at night. I once tentatively pointed out that Slocum had managed it. Moreover, he had been alone while Seth and I were two on board. We could stand four-hour watches and thus be fresher than Slocum could have been. “But in Slocum’s day there wasn’t so much shipping traffic,” countered the person warning us that morning. “All the shipping in the channel is an added problem, on top of the coral.”

|

|

Approaching Snapper Island, north of Port Douglas. |

“If it’s a shipping lane, though, it must be well marked,” I said.

“But it’s narrow in a lot of places.”

“Yes, I can see how that would be nerve-wracking.”

I could, too. No sailor likes to be close to a fast-moving ship in a narrow channel at any time, especially not at night. The people dissuading us from a non-stop passage were also correct that Queensland’s reef system poses perils that should not be overlooked. After all, Capt. James Cook’s ship Endeavour was badly stove in on these shoals. This was even after he had taken the precaution of deploying two shallow-draft boats constantly ahead of his ship, sounding for reefs.

Despite the warnings, Seth and I still hoped to follow in Slocum’s wake and sail the last 300 miles of the passage in one shot. But to placate our advice-givers, we ceased to mention it, saying only that we planned to do the first portion in day hops. The Queensland coast is too beautiful to pass by without stopping at all.

In Cook’s wake

Tropical North Queensland, the area extending from Cairns (16° 55’ S, 145° 47’ E) to Cape York (Australia’s northernmost point at 10° 41’ S, 142° 31.8’ E), combines wild hills with lush coral, quiet anchorages, and sheltered water dotted with islands. It is arguably some of the loveliest coastal cruising in the world. But to enjoy its beauties, voyagers must have good charts and reliable navigation equipment including that always useful tool, a depth sounder. It is also prudent to have one’s yacht in good voyaging condition. The region is remote and largely unsettled — there are no boating facilities north of Cairns and Port Douglas — so it is not an easy place to do any major repairs.

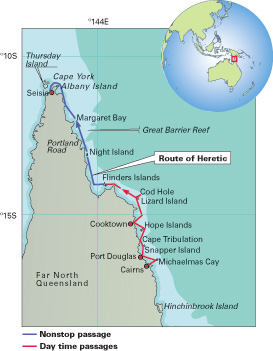

Since cyclones pound the Queensland shore from November to late April, cruising here is only safe in the Southern Hemisphere winter, from May through October. Once hurricane season sets in, it is best to be either south of the cyclone belt (many voyagers spend the summer in Sydney), or north of the belt in Southeast Asia or Micronesia. It is even possible to cruise along the Great Barrier Reef for two or three months and still cross the Indian Ocean to reach cyclone-free South Africa the same year, which is the route Heretic followed.

|

|

Ellen and Seth Leonard‘s sloop Heretic at anchor off Snapper Island. |

Cairns is a good point at which to begin the voyage north. It is a port of entry into Australia, and Seth and I found the customs officials friendly and efficient. A bus system makes Cairns a practical place to provision and even services the industrial zone if one requires boat parts. There are a few marinas, and it is also possible to anchor across the harbor.

It is easy to get away from the city life of Cairns. A bus ride away is Barron Gorge National Park, replete with hiking trails through the tropical rainforest. And just a short sail away, 20 nautical miles east and not far from the Outer Reef, are a collection of sandy cays rimmed with coral. The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority provides public moorings at these cays and at many other places along the coast, although a four-hour time limit usually applies. But if a vessel picks up a mooring at 1500, she is allowed to stay until 0900 the next morning.

|

|

Ellen and Seth Leonard broke their inside the Barrier Reef trip into two parts. In the southern region they anchored every night. North of Flinders Island they sailed non-stop. |

Color-coded moorings

The moorings are blue with color-coded bands according to the type and length of boat they can accommodate and in what wind speeds: a mooring with a green band, for example, can hold monohulls of up to 65 feet in winds under 34 knots. The Marine Park Authority indicates the location of the moorings on their website www.gbrmpa.gov.au. They also publish free zoning maps showing what activities are prohibited in each area of the reef, mostly with regard to fishing. All the zones except the pink-colored Preservation Zone permit boating, diving, and photography. Heretic spent the first night of her cruise on a Marine Park mooring off Michaelmas Cay.

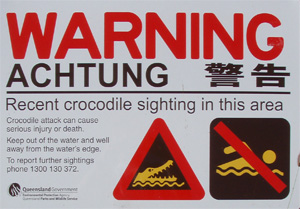

From Michaelmas Cay, we sailed north to Port Douglas, the last real town on this wilderness coast. About 40 miles north of Cairns, it has a historic section and an impressive aviary where one can “lunch with the lorikeets” and see the flightless cassowary, an enormous prehistoric-looking bird with a bright blue neck. The yacht club provides a dinghy dock, and the port has a chandlery and other yacht services. There is a large marina, but Seth and I chose to anchor in Dickson Inlet where fish eagles and rainbow bee-eaters landed in the mangroves. A saltwater crocodile was a resident on one muddy bank, but he seemed more frightened of our dinghy than we were of him.

Leaving Port Douglas behind, we set sail for Snapper Island, a hilly crumb broken off from the coast. We picked up the Marine Park mooring and went ashore for a stroll on the deserted beach: Snapper Island is a national park and is uninhabited. The calm night was silent except for water lapping on the hull. Heretic was as alone as James Cook’s Endeavour was in these same waters 239 years before us.

|

Cape and mountain misnamed

The next day we rounded Cape Tribulation. For Cook the headland was where his troubles began; soon after seeing it, Endeavour was badly stove in on a patch of coral. Cook and his crew initially despaired of saving their ship, hoping only to reach two sandy islets they could see. There they thought they might fashion a boat from the ship’s materials to take them to Batavia (modern Jakarta.) With four large pumps working hard, however, Cook was able to pass the Hope Islands and reach the mainland where his crew hauled Endeavour ashore. The carpenters repaired her and she eventually continued back to England. But for us, Cape Tribulation was reflected in a mirror-like calm, and we anchored in its quiet lee for a hike up the nearest hill, regrettably called Mount Sorrow. From atop its ridge, we could see green hills to the south and the line of breakers on the Outer Reef to the east. As we spent another tranquil night in another empty anchorage, it seemed that for us at least, both the cape and the mountain had been misnamed.

|

|

A sign warning of “salties,” saltwater crocodiles that live along the coast. |

The Hope Islands lie 20 miles north of Cape Tribulation and are a pair of low-lying cays surrounded by reef uncovered at low tide. Although in her dire straits Endeavour passed them by in favor of Endeavour River, today they offer a pleasant night’s stopover for yachts. The anchorage is off the eastern side of the two islets, and it is wise to make the approach through the shoals carefully and in daylight. Mangroves blanket the western island, but the eastern cay is girded in white sand. Fish eagles roost in the shrubs in the center of the island, and the reef at low tide is a hunting ground for snowy white egrets and blue herons. Sea cucumbers, brittle stars, and little eels inhabit the tide pools.

Continuing in Cook’s wake, Seth and I reached the Endeavour River the next afternoon. The entrance crosses a shallow sandbar, so Cooktown is really only an option for boats with six feet of draft or less. Even with Heretic drawing four and a half feet with her centerboard up, we managed to run hard aground at the end of the dredged channel. The channel itself was well marked, but the anchorage beyond was guesswork. Fortunately we went aground on soft mud on a rising tide. Seth and I rowed out our 55-pound CQR and waited to float. But a local man noticed Heretic listing at an awkward angle and offered to take us around the harbor in his flat-bottomed skiff to find a good anchoring spot. Looking at his depth-sounder, we discovered that deep water continues upriver from the buoyed channel close along the southeastern shore, the town side. With this insider knowledge, the anchorage was no longer a guessing game. When the tide floated her, we moved Heretic to a spot near the dinghy beach and within view of the boulder marking the spot where Endeavour was hauled ashore. Like Slocum during his stop in Cooktown, Seth and I wondered how the modern inhabitants could possibly have known the exact location of Cook’s repairs. In Sailing Alone Around the World, Slocum mentions facetiously that Cook must have had a dredger with him if he had truly put his ship ashore where the marker stood.

After Endeavour’s visit, the Aboriginals in the area remained largely undisturbed until Cooktown’s inception in 1873 as a gold rush boom town. But the bustle of the 1870s has faded, and Cooktown today is a sleepy village of less than 1,500 residents. There is a small grocery store and a few pubs, but it is mostly a place for exploring the wilderness. Walking trails lead 1,400 vertical feet up Mt. Cook, and wild kangaroos hop through the old botanic garden. A nearby wetland is home to many birds, including the comb-crested jacana that walks on lily pads. And there are several picturesque bays with soft sand beaches set between steep headlands. But as hot and dusty as hiking is, swimming in the waters around Cooktown is risky. The ferocious saltwater crocodiles that inhabit the coast can grow up to 20 feet and 2,000 pounds.

|

|

Ellen and Seth did some coral reef diving during their passage north. |

Since Seth and I had been sailing in crocodile-infested waters since Michaelmas Cay, we were eager to find a place safe to swim again. A few days later we set off from Cooktown for Lizard Island, 50 miles to the northeast and which Cook had named for the giant sand monitor lizards that still live there. Lizard Island is a national park and is popular among voyagers for its snorkeling and pristine beaches. Seth and I anchored a short swim away from a reef alive with clownfish and giant clams. A walking path led across the island to the Blue Lagoon where sea turtles poked up for air and cuttlefish inked in the shallows. Another track through mangroves and pandanus ended at the Lizard Island Research Station where we listened to a talk about the threats of ocean acidification and rising sea temperatures to coral reefs. And only 13 miles to the northeast are the moorings for Cod Hole, a dive site on the Outer Reef renowned for its enormous potato cod, colorful corals, and pelagic visibility. Besides the snorkeling, trails meander all over the island, and no visit is complete without a hike up the highest hill to Cook’s Look, the place where the famous navigator looked out to sea and found a break in the outer shoals through which he could steer Endeavour.

|

|

Ellen Massey Leonard takes in the view atop Cook’s Look on Lizard Island. |

A well-marked passage

If one wishes to continue the passage in day hops, there are several anchorages north of Lizard Island, but Seth and I stopped at only one of them: the red and rocky Flinders Island where we visited a cave covered in Aboriginal rock art. North from Flinders is Night Island, Portland Road, Margaret Bay, and Escape River. Seth and I judged some of these, Portland Road in particular, to be too exposed to the southeast trades and decided to make a continuous passage to Cape York.

Up-to-date charts and automated flashing navigation markers make the passage straightforward, and we thought it was preferable to anchoring off an exposed coastline. It is important, however, to keep a careful watch at all times and be ready to change course and sail plan more often and more quickly than is usually necessary on an ocean crossing. There was no doubt more shipping than in Slocum’s day, but the channel never narrowed so much that this was a problem. We kept Heretic on the right-hand edge of the lane in order to let northbound ships overtake us easily and to pass southbound ships port to port.

The final challenge, faced by passagemakers and day-sailors alike, are the tides coming through the Torres Strait around Cape York. We chose to go out and around Albany Island rather than through the narrower Albany Pass between it and the mainland. We timed our sail for the flood and roared around Australia’s northern tip at eight knots. There are two popular anchorages in the Torres Strait: Thursday Island where one can clear customs out of Australia, and Seisia, a village on the western side of Cape York. Seisia lacks the strong tidal currents that pass by Thursday Island, but it is not a port of entry, so one must continue on in Australia in order to clear out. In the Northern Territory, Gove and Darwin are exit ports, and there are also several in Western Australia. Seth and I chose to clear out in Darwin, so we anchored off Seisia. By late afternoon less than three days after leaving Flinders, we were rowing ashore for ice cream. We had enjoyed both parts of our voyage: feeling our way slowly north as Cook had, and running fast before the wind night and day just like Slocum.

——————-

Ellen Massey Leonard is a freelance writer who recently circumnavigated with her husband Seth on board their former boat, Heretic, a 38-foot sloop.