To the editor: If you had business in the deep Caribbean Sea in 1960, you needed at least a rudimentary knowledge of celestial navigation. GPS was not in the inventory. On our voyage across the Caribbean, we had to find Curacao using a sextant — the accuracy of which was questionable due to my momentary lapse of attention.

We were aboard the 100-foot West Coast combination-fishing vessel Oregon, which flew the duck and salmon pennant of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Commercial Fisheries. We were tracking that mysterious, sleek and incredibly fast monster: the bluefin tuna. Our mission was to inventory marine resources in the Gulf, the Caribbean and the southern North Atlantic Ocean down to the bulge of Brazil.

Oregon operated from Pascagoula, Miss., with a crew of 10 stalwart characters of various backgrounds, and a usual scientific party of two or three. On this cruise, we also had Frank Mather of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution — the world’s expert on the migration of bluefin — and Mark Rascovich, a writer for the Museum of Natural History.

I was the ship’s new guy, with a recently awarded Master of Science degree from the Southwestern Louisiana Institute. My official title was “Fisheries Methods and Equipment Specialist.” Because of my Sea Scout training in celestial navigation using Warwick Tompkins’ fine little book, The Offshore Navigator, I was unofficially designated second mate and assistant navigator.

Captain Johnnie H. Tyler, from the Mississippi hinterlands, was a licensed master mariner with a most un-nautical bearing and poor eyesight. He needed me to take sights with the sextant. We had one surplus standard Navy instrument and a decent chronometer. We also had a state-of-the art Simrad deep-sea sounder and fish finder, which was a valuable navigation aid.

In a research vessel like Oregon, the captain was responsible for the safety, navigation and supervision of the crew, but the man who was really in charge was the field party chief (FPC). On this cruise in April of 1960, the FPC was the salty ex-Provincetown offshore fisherman Francis J. Captiva (Kaki). Kaki was a first-class fisherman, but he lacked any real knowledge of navigation by sun and stars. Getting where we needed to go was up to Capt. Tyler and me.

Our plan was to go to Curacao in the Lesser Antilles and fish parallel to the Venezuelan coast as far east as Trinidad. After leaving Trinidad, we planned to head north and then west along the Lesser and Greater Antilles, searching for bluefin. First we had to cross the open Caribbean to make Curacao.

Capt. Tyler was in his 50s and a “self-educated” seaman. I was convinced that Tyler was either a backwoods genius or a quack. He was a pretty good ship handler, but he used reams of yellow legal pads to make celestial navigation calculations. I could never follow his secretive figures and he was not forthcoming with explanations.

To take our morning line of position, Capt. Tyler took the necessary sun azimuth and he did his calculations. My job was to measure the sun’s noon altitude with the sextant.

|

|

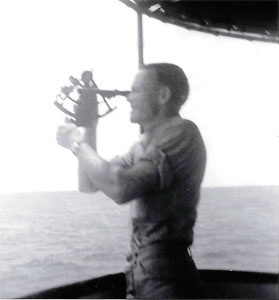

Charles Fuss taking a sight on the bridge of Oregon while in the Caribbean. This was likely before the “sextant incident.” |

|

Courtesy Charles Fuss |

When we got south of Haiti, headed for Curacao, the trade winds found us again and our roller coaster ride resumed. A deck hand and I kept the 0400 to 0800 watch. I was also expected to be ready for the noon sun altitude.

I fell from grace on the first day of our deepwater passage to the southeast. Oregon was even more lively than usual. I had already taken the morning sun line altitude when Capt. Tyler and I staggered into the chartroom and I foolishly put the sextant down on the chart table. I knew I needed to clean the salt spray off the eyepiece lens and the index glass. We didn’t see the huge sea coming. It hit us on the port beam and we nearly rolled the bridge rail under. I made a desperate grab for the sextant; it shot past me like a cannonball and landed with a clatter on the deck of the pilothouse.

I scurried to retrieve the sextant. Capt. Tyler turned away from the chart table with a blank look. “Isn’t that a delicate instrument?” Rascovich asked. He was shocked. Mather asked the captain if he had another sextant. Tyler admitted that we had only the one but assured our guests that we would “superimpose the moon” and he would calculate any error that the instrument may have acquired from its fall. Our guests looked exceedingly skeptical. They knew we had to use the sextant to find Curacao.

The captain and I examined the sextant and found the eyepiece was stuck in the frame, but miraculously no glass had broken. Capt. Tyler, bless his quirky heart, never blamed me for dropping the sextant. He told me not to worry, but that the eyepiece had to be unscrewed so the instrument could fit into its wooden box. Tyler said to follow him down to the machine shop where we would make some adjustments. He sent me to fetch a towel. He wrapped the sextant in the towel and placed it in a vise! Tyler gripped the stubborn eyepiece with a small pipe wrench and backed it out of the instrument frame. There was a lot of noise from the engine, so at first we didn’t see Mather and Rascovich standing just aft of the bulkhead watching us. The captain growled, “Just ignore them.”

That night we had a good moon and the sky was clear of interfering clouds. Capt. Tyler and I climbed to the top of the pilothouse with the sextant. I followed his instructions, lying on my back and lining up the lower limb of the moon in the horizon and index glasses. I guess it was comparable to a “lunar index error” measurement. Perhaps Tyler figured we could see the moon better. At any rate, he took my measurement and completed some of his inscrutable calculations. The result was a small correction that we would apply to all altitude measurements for the rest of the voyage. I said a prayer to St. Jude, the patron of hopeless causes. I was doubly concerned because my wedding date to my fiancée, Carol Ann, was approaching and we were due to return only two days before that event.

We labored across the trackless open and windy Caribbean Sea toward our intended destination. Each day the pressure grew, at least for me. The captain seemed superbly confident that our navigation was accurate. Every evening, Mather and Rascovich had their cocktail on the narrow deck outside their stateroom (contrary to regulations prohibiting alcohol on government vessels) and cynically discussed our progress. I overheard Rascovich say, “Whoever heard of working on a sextant with a pipe wrench?”

We estimated our time of arrival at Curacao on the afternoon of our third day after leaving the Haitian coast. I had a hard time eating lunch that day. Although I was not on watch, I spent the afternoon scanning the horizon. My eyes were bugging out and my arms were sore from holding the heavy Navy binoculars. Capt. Tyler went about his business unconcerned.

The mate, Howard King, saw it first. He asked, “Charlie, what’s that up there a little to the right?” It was one of the finest sights that I had experienced in my 29 years. There it was! We could barely see the squat Noordpunt Light on the northwestern end of Curacao atop a high bluff some 138 feet above sea level. Then and there, I decided Captain Johnnie Tyler was a backwoods genius. We strutted about the bridge in front of our guests like a couple of bantam roosters.

We circled the Caribbean and made some tuna history. Thank God I got home in time to marry Carol Ann (she had to get the license and rings). Frank Mather went on to become famous as the father of the tag-and-release program for big game fish. Mark Rascovich later wrote The Bedford Incident, a best-selling Cold War naval thriller, in 1963. In 1965, his book was made into a movie of the same name, starring Richard Widmark and Sidney Poitier.

—Charles Fuss is a retired NOAA scientist who lives in St. Pete Beach, Fla.