Only a few decades ago the only communication options were VHF radio and high-frequency single sideband (HF SSB). Today that list is a bit longer with cellphones, Wi-Fi and satellite communications now available on many boats. Each of these has its own benefits and its place aboard a voyaging boat, but I have found the old ways are, if not the best, then sometimes the most fun. Many boats have a marine SSB radio, which is very similar to amateur (often called “ham”) radio. Although equipped with these radios, many are not getting as much out of them as they could. Using marine SSB and ham radio aboard your boat can add a new dimension to communication, opening up new sources of information and, sometimes, new friends along the way.

So what is ham radio? It is a type of AM radio and is very similar to marine SSB. Ham radio operates on similar frequencies to marine SSB; however, it allows more frequencies to be used, making it much more versatile. Operating on the AM bands means that with just a relatively small amount of output power, you are able to communicate long distances, sometimes thousands of miles, making this a good option for voyaging boats in far-off locations. In fact, ham radio is so similar to marine SSB that almost all marine units can be “opened up” to amateur bands with just a simple software update.

|

|

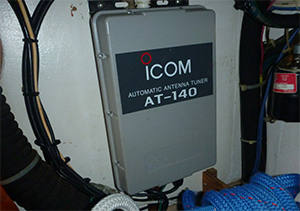

An automatic antenna tuner. |

Many cruisers, both power and sail, have found that amateur radio can not only add a new level of safety to their cruising but can also add a new dimension of fun. One of the big differences in radio communication versus using a cellphone and satellite phone is that it is open for others to hear and join in on the conversations. Now at first this lack of privacy may seem a bit uncomfortable, but in truth it opens a new community to the cruiser in their travels. There are many “nets” or open conversations available to any cruiser who wishes to join in. Information about weather, cruising conditions and even boat repair is talked about on these radio nets. Many nets have a daily “check in” for voyaging boats on passage, adding to the safety factor for these sailors. Most of these nets operate at specified times of the day and are controlled, meaning a volunteer will “direct traffic” and determine who can talk and when.

Almost there

If you already have a marine SSB, you may be very close to being able to use the amateur frequencies as well. As mentioned, most marine SSB units can be modified to work as a ham radio. This modification is usually a simple software mod that can be made by any good marine radio technician. The antenna and antenna tuner remain the same, so this can be a very cost-effective way to get into amateur radio. If you are starting from scratch, it is recommend to install an already opened marine radio as these are simpler to operate and can also be used on the marine bands and frequencies. FCC laws allow users to operate a marine radio on the ham bands but not the other way around, as marine units are required to have tighter tolerances for maintaining frequency during operation.

Many are put off by the complexity, expense and difficulty of getting set up with ham radio. The equipment can be pricy and the installation a bit finicky but not that difficult. Add to that the need for a license and many pass up becoming a ham radio operator. It is true that getting set up for amateur radio communications can be a bit daunting, but it is usually worth the effort. It also needs to be kept in mind that most amateur radio services are free, unlike satellite and cellphones that require a monthly fee to use. To reduce costs, there is also the option of purchasing used equipment. For others, the thought of having to study Morse code along with electrical and radio theory to get the license is too much. The truth is that Morse code is no longer required to get a license.

There are three basic levels of ham radio licenses available in the U.S. Each level gives the operator more frequencies and privileges when operating an amateur station. The first level is a technician license; this is an entry-level license with fairly restricted use. The next level is a general class license, which is what most cruisers get. This license opens more frequencies for the operator. Finally there is the extra class license, which requires an even greater level of understanding of theory. This license has 50 questions and you must pass the previous two tests before you are allowed to test for this. The extra class license does open all amateur frequencies to the operator, giving you even more options.

|

|

While it’s possible to use a fiberglass whip antenna for HF SSB radio, most sailing vessels electrically insulate a section of the backstay for use as an antenna. |

License testing

Both the technician and general class licenses only have 35 multiple-choice questions to pass and neither requires Morse code anymore. You must pass the technician class test before you can test for the general class. This means you only have two tests with a total 70 questions to be up and running with an amateur station. What you learn can also be helpful to understanding the rest of your boat’s electrical systems, so it’s not a bad investment of time.

Taking the tests is usually very simple. The tests are given by local American Radio Relay League (ARRL) groups and are normally given every other week or at least once a month depending on your location. The fee is low and you can take both the technician and general class tests in the same sitting for the same fee. You must pass the technician test prior to taking the general class test, but they can score your test right there and let you know if you can take the next test right away. This can save a few bucks too, as you only pay a single testing fee. After passing the tests it only takes a week or so to get your call sign, which allows you to operate on the air.

There are many online resources to aid in studying for the tests. Many have sample tests that you can take to help get you ready as well. The ARRL website has a lot of information on just how to go about the whole process. For most voyagers, a couple of weeks of study in your spare time is all it takes to get through the tests. For many cruising couples this can be a fun way to prepare for your upcoming voyages.

Setting up a station aboard your boat can be as simple as modifying an existing marine SSB unit or a bit more challenging for those starting from scratch. For those with an existing SSB unit, check to see if it is possible to transmit on an amateur band. To do this, you simply tune to a non-marine frequency with no traffic on it and key the mic; if the radio goes into transmit mode, you are good to go. If it does not, you may need to make a modification to the radio. How difficult this is will depend on the brand and age of the unit. It would be best to consult a local marine radio technician for help with this, but some information can be found online as well.

For those starting from scratch, I recommend purchasing a marine unit that is already open to the amateur bands. Installing an SSB radio is not quite as easy as installing a VHF radio, but it is not as difficult as some would have you believe. There are basically two parts of a good installation: the radio itself and the antenna system. Notice I refer to the antenna as a system rather than a single element. This is because the antenna is perhaps the most important part of the installation and is a bit more than just a pole stuck up on the top of the boat. SSB antennas consist of basically three parts; the first is the antenna itself, next is the antenna tuner and, lastly, the antenna ground plane.

It is beyond the scope of this article to get into all the nuances of antennas and radio installation, so I would suggest you find a good technician to help with the installation. Check with your local amateur radio club and other boaters in your area that use marine SSB for advice. I do recommend keeping things as simple as possible and building on a basic installation as your expertise with this type of radio grows. Do not cut corners on wire or wire connection quality as these are critical. When helping troubleshoot problems on other systems, I have found it is often the very simple basic things such as using a poor quality antenna cable that can make a system not work at all.

|

|

Some marine HF SSB radios can be easily modified to broadcast on ham frequencies. |

A new world to explore

Once you have your radio set up and have passed your tests for your license, it is time to explore this new world of amateur radio. For many this means sitting in the marina trying to make contact with someone. This is also the point where many get frustrated and begin to lose interest from the start. The problem is most marinas are very noisy as far as radio signals go. Other boats’ refrigerators, battery chargers and other equipment leak radio noise; add to that transformers and other equipment in the marina itself, and nothing but the strongest signals get through to your radio. Another mistake many make is not knowing where and when to try to talk to other stations. It is at this point many think their installation is poor when in fact it may not be.

Before getting frustrated, it helps to search online for the times and frequencies of marine nets in your area. Try just listening for a bit, pick a few nets to follow and tune in when they are on. If all you can hear is static or strange beeping noises, try turning off equipment on your own boat to see if this quiets things down. Inverters, battery chargers and refrigeration units are among the noisiest things aboard. If this does not help, try taking the boat out of the marina and try again. It can be amazing the difference just anchoring out away from all the electrical noise can make. Connecting with another amateur radio operator in an online group who you can set up a time to talk to is a good way to test your setup as well. If all else fails, try contacting your local amateur radio club for help. These people love to assist newbies in getting going, and will be more than willing to check your setup.

Setting up for amateur radio may seem a bit formidable, but it is not as hard as some think. The rewards come when you get to share information and make new friends while cruising the marine nets. As you begin to listen to and participate in the cruising nets, the names of the boats and their crews will start to become familiar. You may even find yourself anchored in the same cove as someone you have been talking to. Often the net controllers are land based, giving them access to weather and other information that might be hard to get while afloat. These net controllers can also be helpful in keeping contact with loved ones at home. More than once I have heard emergency information relayed when someone at home became ill. You can also get real-time information about port conditions and other safety matters.

The use of amateur radio aboard your boat can add a new dimension to the cruising experience, adding safety along with a bit of fun in the process. Learning to install and operate the equipment will add to your overall boating electrical knowledge. The expense and learning curve are not as bad as some would say, and the rewards are many.

Wayne Canning (KJ4WXF) is a marine surveyor and author currently based in Cape Coral, Fla., aboard his sailing vessel Vayu. He operates both an Icom IC-M710 marine radio and an Icom IC-718 amateur radio while aboard.