Editor’s note: This is the third part of a multipart series, “The toughest passages of 50,000 miles,” a look at the most difficult aspects of circumnavigators Ellen and Seth Leonard’s various ocean voyages.

In the midst of our second Pacific crossing last year, my husband, Seth, and I crossed the equator for the third time. I had not been looking forward to it. Possibly more than anything else at sea, I fear lightning. Possibly the scariest situation I’ve encountered on a boat had to do with lightning. It was arguably just as frightening as the high breaking seas we weathered off South Africa on our circumnavigation (“Worst weather challenges,” September/October 2019, Issue 257). It happened a number of years ago, but the fear hasn’t gone away. It is, after all, a rational fear, given that a sailboat in a thunderstorm is a sitting duck.

On the flat expanse of ocean, far from land, a sailboat’s mast is essentially a giant lightning rod. It’s the only tall thing for miles and miles around. Even if the boat is grounded, this is a scary situation. I personally know one sailing couple — and I know of others — whose boat was hit by lightning. Their boat was fortunately well grounded and thus did not sink, but the boat’s interior was heavily damaged and all their electronics destroyed. They were at anchor and not on board at the time, so this was less of a problem than it might have been had they remained on their vessel. And this is the best-case scenario.

|

|

Ellen Leonard’s boat Celeste in the doldrums where lightning is a factor in squalls. |

Before I started sailing offshore, I was not afraid of thunderstorms. Thirteen years and over 50,000 sea miles have changed that.

For the first part of our circumnavigation — from Maine to the South Pacific — Seth and I had very good luck with this type of weather. Our first experience with the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), colloquially known among sailors as “the doldrums,” was wonderfully benign: En route to the Galapagos from Panama, a light southerly wind allowed us to sail the entire passage and the overcast sky never developed into thunderheads.

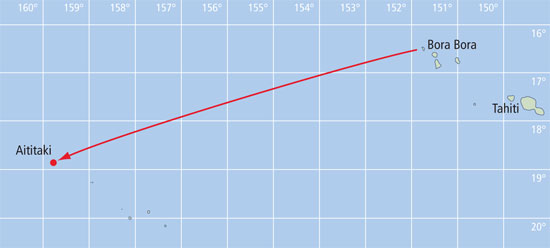

It was only upon leaving Bora Bora in French Polynesia for the Cook Islands that we first encountered lightning. After two days of strong trades, the wind became unsteady, the sky overcast and the air heavy. As night fell, white currents of electricity flashed between the clouds all around us. The lightning wasn’t grounding, but we were scared it might. Spying a gap to the south, we changed course and put on sail, trying to get away from it. Nothing bad happened; by morning it was clearing and we were approaching Aitutaki Island. But it had been a stressful night.

|

|

On a passage to Aitutaki Island, the Leonards were surrounded by lightning clouds on their last night. |

Flashes to the north

We got lucky again during our second season in the Pacific, sailing from New Zealand to Australia via Fiji and Vanuatu. The South Pacific Convergence Zone can sometimes bring ITCZ-type weather to these archipelagos, but we had only occasional squalls and cloudy skies. And then on our Indian Ocean crossing, the scary thunderstorms were well north of us in the Asian monsoon region, and we barreled along before blustery trades.

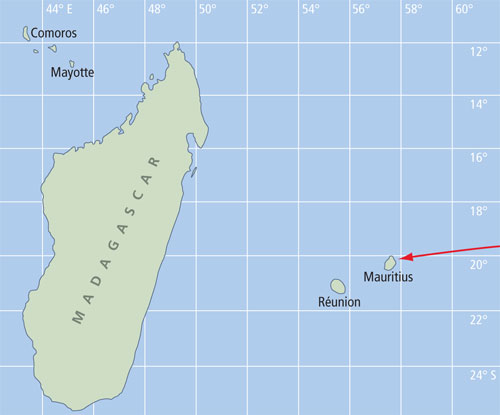

Aside from the ITCZ, lightning tends to happen close to land. As we approached Mauritius Island, about 600 miles east of Madagascar, the lightning started. This time it was grounding, purple forks sizzling into the sea, loud rumbles of thunder right on top of them. That was the first time that Seth and I knew what it felt like to be truly frightened at sea. What if the grounding we’d done for Heretic wasn’t good enough? Any strike would find the fastest way to water through our 1968 fiberglass cutter. That could be right through the hull, pricking thousands of tiny holes at the waterline and sinking us. And even if the ground was sufficient, what would happen to us in the force of the strike? What about damage? On our shoestring budget, it seemed unlikely we’d be able to afford to repair and replace everything that could be fried, and our circumnavigation dreams would end right there in one flashing moment.

Dodging the thunderheads, we passed a tense few hours while the storm roiled around us. Finally it passed us, climbing up into the hot tropical mountains of Mauritius to frighten the people on shore. By mid-morning, we were turning into the port of entry, tired but very relieved.

|

|

While crossing the Indian Ocean, Heretic experienced more close calls with lightning. |

Lightning in the Chesapeake

Our next encounter with lightning, our most terrifying, came two years after we’d completed our circumnavigation. We had sold Heretic in 2010 upon our return to Maine, but by 2012 we were looking for a replacement — something smaller on which we planned to gunkhole up and down the East Coast in summer. We found a lovely 34-foot wooden ketch, modeled on an L. Francis Herreshoff design, in the Chesapeake Bay. She needed a fair amount of work, but after all the repairs and upgrades we’d made to Heretic, we weren’t daunted and soon had her in decent sailing shape.

We had enjoyed clear skies, good wind and pleasantly cool temperatures in the weeks we’d been in the Chesapeake working on the ketch. So, to be honest, thunderstorms were very far from our thoughts. They shouldn’t have been: The southern Eastern Seaboard has some of the highest incidences of thunderstorms of anywhere coastal, excepting Indonesia and Southeast Asia. Anyone who has been held up at the Washington, D.C., airport is aware of this. But in the cool, clear weather, we’d simply forgotten, and so neglected to ground the ketch’s masts before we took off for a cruise of the Chesapeake.

The cool, breezy weather continued for the first few days as we made our way north toward the Chesapeake & Delaware (C&D) Canal. Because of the tides and currents, our plan was to transit that waterway around 2 a.m. and sail through the night down the Delaware Bay to Cape May, N.J. We intended to anchor near the canal before nightfall; we set our alarm clock so that we would make the tide.

|

|

Radar shows squalls ahead. |

That afternoon, as we sailed north, the weather changed — fast. Suddenly the wind died and the air felt hot and muggy for the first time in weeks. The sky clouded over in a strange, sullen, brown color. It all felt very ominous and for the first time we remembered this region’s reputation for summer lightning.

Tuning the VHF to the Wx channel, we found that the previously benign forecast had changed drastically. Gale-force winds and “prolific cloud-to-ground lightning” were expected, the disembodied National Weather Service voice told us. We learned later that the recorded wind speeds in fact topped 90 miles per hour, much more than gale force, and had been dubbed a “land hurricane” because the wind had swung around the compass so quickly. The storm had also blacked out Washington, D.C., though of course we couldn’t have known any of that beforehand.

We decided to anchor where we’d originally planned, as it was protected by rising ground, something not always easy to find in the low-lying Chesapeake region. There wasn’t much else we could do. We set our 60-pound anchor in less than 10 feet of water (our ketch had a shallow draft of less than 5 feet) and let out 75 feet of 5/16-inch chain. We had to do the best we could with a quick-and-dirty ground for the masts. Stripping the insulation off the ends of some heavy-gauge wire we had left over from replacing and rewiring the batteries, we clamped it to the shrouds, ready to toss the other end into the water when the lightning started. We put a hand-held GPS, VHF and our cellphones into the oven, the best Faraday cage we could manage. The air was dead still, hot and suffocatingly humid.

|

|

A leaden sky in the Chesapeake augers the possibility of lightning. |

Very soon after dark, the thunder came. At first it sounded a little ways off, but all too soon it was on top of us, the lightning forking down to the land and sea around us so fast that it lit the whole sky in eerie white-purple. Wind came too, fast and strong. It curved around the compass and soon we had dragged ashore, despite all our chain, our plow anchor leaving a furrow in the mud (we now use a “new-generation” Mantus anchor). The wind was kicking the shallow Chesapeake into a nasty chop, slamming our ketch’s stern into the gravel with a horrible grinding noise. The thought crossed my mind that the rudder was probably being beaten to bits. But it didn’t really matter, as it seemed inevitable that one of these terrifying purple thunderbolts would strike us, probably setting our little wooden boat on fire. I wasn’t sure we’d survive; water is very conductive, so trying to swim ashore was not an option until there was no other.

Lasting forever

It seemed to last forever, but finally it was over. The lightning and thunder moved on and the wind died down. The clouds even began to clear and a few stars peeped out. Our ketch listed at a crazy angle in just a few feet of water, but we’d survived and she’d survived.

As we sat there, drained of fear and adrenaline, absorbing our escape, a man came wading out from the shore. He wanted to make sure we were okay. A lightning bolt had struck a tree right next to his house and it had fallen on his roof. He was surprisingly cheerful, though, probably also amazed and relieved to find himself alive and uninjured. We hashed out the storm together in a dazed conversation, which was the type of relief we were all looking for right then.

|

|

The C&D Canal runs between the Chesapeake and Delaware bays. |

A little later, with our energy returning, Seth and I managed to winch our ketch back out into deeper water, taking the anchor chain back to the primary winches as the boat had no anchor windlass. Just as we had her floating again and were trying the tiller to find if our rudder still functioned, our alarm clock rang. At first we didn’t know what it was, but then we realized that it was 2 a.m. and the tide was turning in our favor to go through the C&D Canal. It was surreal. It felt like we’d been through a lifetime of experience in those hours, and here we were finding that we were still on our planned schedule.

The rudder seemed to be working, so why not? We started the engine and went through to the Delaware Bay, still shaking our heads that we were alive at all, let alone that our cruise was proceeding as planned.

Thunderheads off New Jersey

Not so fast, though. Upon reaching Cape May, we decided to accelerate our cruise and get up to colder, less thunderstorm-prone New England as soon as possible before the hot summer weather advanced further. We would make a nonstop passage to Block Island. But as night fell off New Jersey, the lightning began again, with thick thunderheads piling all around us. The ketch was equipped with a good radar, unlike our previous cutter Heretic, and so we could see exactly where to go to dodge them. That benefit was perhaps outweighed, though, by the density and ferocity of the anvil clouds, making our encounter off Mauritius look like child’s play. And it kept on and on. We stood watches as usual, but the watch below turned in wearing full foul weather gear, expecting any moment to be on deck. We’d had one day of respite sailing down the Delaware, and here we were again, surrounded by lightning.

Fortunately though, with the help of our radar, we managed to dodge the countless thunderheads, and by the early hours of the morning the land had cooled sufficiently to dissipate them. We reached Block Island, and then Maine, without further incident and with our love of ocean sailing still intact.

|

|

Ellen planning the Chesapeake cruise before the big thunderstorm. |

Our East Coast gunkholing idea, however, didn’t hold up so well to these stormy onslaughts. We sold the ketch the following year and bought Celeste, a seagoing cold-molded cutter, in British Columbia. For five summers, we voyaged throughout the cold and rugged waters of Alaska, ranging up to the polar ice edge. Alaska does get thunderstorms when the interior heats up in summer, but very rarely do they occur on the cool coastline where glaciers still touch the sea.

So, as Seth and I sailed Celeste toward the ITCZ on our second Pacific crossing, neither of us relished the thunderheads on the horizon. Unlike the ships of the Age of Sail — which might have wallowed in these windless latitudes for weeks, their water running low and their crew getting scurvy — Celeste, like most small voyaging boats today, has an auxiliary engine and the ability to receive good weather forecasts. As soon as we entered the doldrums, we changed course to cut across it at right angles. We knew the correct course to steer from studying our weather files. Whenever our boat speed fell below 3 knots, we started the engine — we had stocked up on diesel fuel before leaving Cabo San Lucas in Mexico for just this purpose. In this way, we transited the ITCZ in the shortest time and distance possible. The air flickering with cloud-to-cloud lightning still weighed on us, but between the radar and the engine, we steered clear of the worst squalls and thunderheads.

Eventually, we were through and into the southerly trades. They were too strong and too far ahead of the beam for pleasant sailing, making us reef down and plunge into the waves. But both of us would take that over lightning any day.

Ellen Massey Leonard and her husband, Seth, completed a circumnavigation aboard their 38-foot cutter-rigged sloop, Heretic. They were recipients of the Cruising Club of America’s 2019 Young Voyager Award.

|

|

Squalls in the Intertropical Convergence Zone. |