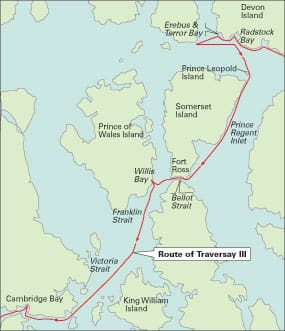

Less than 200 vessels of all sizes from icebreakers on down have successfully sailed the Northwest Passage since Roald Amundsen’s Gjøa made the first transit early in the last century. Some have suggested that this is now an easy route from Atlantic to Pacific with more ice vanishing every year. For us, on our 45-foot steel sailboat Traversay III, it turned out not to be so simple.

Our March 30 departure from St. Katharine Docks in central London gave just enough time to be pinned down a week by weather in the Thames Estuary, for dives to clear away night-time crab trap encounters in Wales, to deal with gales and whisky in Scotland and to make a westbound North Atlantic passage to the west coast of Greenland.

|

|

The steel cutter Traversay III near Upernavik, Greenland. |

All that was just to get us to the starting gate in Baffin Bay. The critical sections of the Northwest Passage only become navigable late in August and new ice often shuts the door again by mid-September. After arriving in Arctic Canada as summer was already waning, we felt the pressure to get moving. We only found out later that 2013 was the worst ice year since 2006. Before that there were no good ice years.

On Aug. 16 at 2300 snow obscured a lonely graveyard on the nearby rocky shore of Devon Island in Canada’s High Arctic. It was not dark outside; just gloomy. Through the deckhouse windows of Traversay III we could just make out the aluminium cutter Acalephe also pitching at anchor in the gale-driven waves. Small chunks of ice drifted about the bay. The staccato of a halyard occasionally beating against the mast punctuated the continual moan of the wind in the rig.

That lonely graveyard was a reminder of Sir John Franklin’s ill-fated expedition in 1845. His ships Erebus and Terror wintered in this bay and a number of crewmembers were laid to rest under this forlorn hillside before the spring came.

Forced out by ice

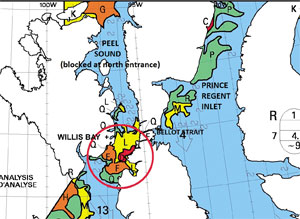

Yet another check of our e-mail added to the gloom and depleted our Iridium satphone account by a few more precious minutes. A new ice chart had just arrived and showed our tenuous hold on security in Erebus and Terror Bay to be short lived. Ice charts are color coded from green meaning “you’re going to have to slalom a bit to avoid the ice,” to red for “this is a lot like trying to sail across an island.” A large band of red showed that the wind was driving ice toward our anchorage.

|

|

Lonely graveyard at Erebus and Terror Bay where members of Franklin’s 1845 expedition are buried. |

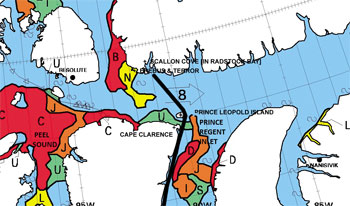

The VHF came alive confirming that Acalephe had just received the same chart. A few moments of conversation yielded the obvious: that we must leave this place. Nick on Acalephe had sailed this part of the world before having been on Belzebub the previous year. Belzebub cruised into the record books as the first sailing yacht ever to make it through McClure Strait. He felt that Peel Sound would not open in 2013 and that the only route west would lie through Prince Regent Inlet and Bellot Strait. We, in our less developed wisdom, still wanted to hedge our bets and keep both routes as “possibles.” We headed for Radstock Bay some five hours away in order to keep both Peel Sound and Prince Regent within reach.

We took turns on deck wearing every available bit of warmth under our windproof foul-weather gear. Our feet were nearly warm in thick Norwegian gift-socks and neoprene deck boots. The diesel-fired Espar heater kept it warm in the cabin, but someone had to avoid those semi-trailer sized chunks of ice floating all about. The temperature hovered just below freezing.

|

|

The levels of ice concentration are shown in different colors (orange is 8/10ths ice and red is 9/10ths). Note ice in Erebus and Terror Bay and the open route through Prince Regent Inlet. |

Scallon Cove nestles in a corner of Radstock Bay near the southwest corner of Devon Island. It is one of those places sometimes described with the phrase “you can’t get there from here.” We picked an anchor spot between British boat Arctic Tern and Swiss Libellule. No anchor spot was really better than any other. Everyone had dragged at least once; everyone was using all their chain. For us, that was 270 feet. Anchoring was followed by yet more waiting.

Libellule’s professional skipper had already impressed us as a bit of a magician. He had managed to get over to Resolute Bay, some 90 miles distant, to replenish his food and fuel through ice that appeared to us impassable — and this in a fiberglass catamaran! We had only managed to deplete our fuel supplies by 20 gallons in a futile attempt at the same exercise.

Our wait was not long. Less than 18 hours after we arrived in Scallon Cove, a new ice map showed Erebus and Terror Bay full of ice. Good that we had left! Not only that — but the same band of heavy ice was threatening to arrive shortly at Radstock Bay. Just as in the previous anchorage, everyone left within minutes of receiving the ice news.

|

|

A polar bear on the ice at Bellot Strait. |

The only route west

With the northern entrance to Peel Sound remaining stubbornly red, Bellot Strait was obvious even to us as the only route west. To get there we had to negotiate a 10-mile band of “green” — one to three-tenths of ice — at the northwest corner of Prince Regent Inlet. This ice first became visible as an “ice blink” when it was still beyond the horizon and then as a thin line of white as we approached the cliffs of Prince Leopold Island. As we passed, birds beyond number screamed and wheeled and dove.

As the ice got closer, it took a great deal of imagination to see any gaps. We doubled the watch on deck. With only three crew — me, my wife Mary Anne and friend Claude — there wasn’t much rest, but we needed one person to hand-steer around the nearby chunks and another to scan with the binoculars and plan a strategic route through the grander maze of ice. Arctic Tern favored a route farther from the land, while Libellule, also ahead of us, figured the answer was to close the coast at or slightly south of Cape Clarence. I opted for the Libellule route; he was a bit farther ahead, said the worst seemed to be behind and was seeing clear water ahead.

It was not really a walk in the park, but after a couple of hours we had passed three fairly solid bands through gaps not much wider than our 13-foot beam and could revert to having only one crew freezing on the deck. We continued south between the Somerset Island coast and a very solid nine-tenths ice a few miles offshore.

|

|

Bellot Strait blocked by ice. |

Eighteen hours after leaving Radstock Bay, I blogged that it seemed warmer. After less than two degrees of latitude! What was I thinking? Well, the water temperature was up two degrees and I could see a few patches of green on the shore. But back to reality … we were heading for Fort Ross to await the opening of a blocked Bellot Strait. The venerable Hudson’s Bay Company (founded in 1670) closed its trading post at Fort Ross in 1948 because of the impossibility of keeping it supplied through the same ice-choked Bellot Strait. And they used real ships!

Something close to darkness replaced the midnight twilight we had experienced farther north in Lancaster Sound. More southerly latitudes and the advance of August had put an end to anything bordering on “midnight sun,” but we could still see the ice. In the early morning with Arctic Tern a mile or two ahead, we both entered Brentford Bay and headed toward the anchorage below Fort Ross.

Too vulnerable

Austrian boat Belle Epoque invited us by VHF to share their spot in an unnamed passage south of Brands Island. We declined, thinking their location was too vulnerable to drifting ice and picked a nearby cove. In the end, their only problem with ice was the young polar bear hitchhiker it nearly brought aboard their boat. Our only problem with ice was the large floe that drifted upon us too quickly for us to get the anchor up. The snubber was already removed. We stopped winding in. Ice pulled on chain; chain pulled on windlass; windlass support exploded; and windlass shaft ended up choked in multiple turns of battery cable and chain as the entire windlass motor rotated around its shaft. Not a good day!

|

|

The Canadian Coast Guard ice breaker Henry Larsen at work. |

Fortunately Claude is a retired mechanical engineering professor who used to design turboprop aircraft engines. This was just his sort of work. So Mary Anne drove our un-anchorable boat around in gentle circles while Claude and I ran back and forth from bow to workroom fashioning and installing bits of wood to support the windlass motor and resist its torque. By dinnertime we found a mercifully ice-free place to anchor and were happy with our work. We could not know it at the time, but two months and many anchorings later the jury-rigged windlass would still be working.

At 2300 on Aug. 20, Acalephe and Traversay III retrieved anchors and headed into Bellot Strait. We felt some trepidation. There were rumors that strong turbulent tidal currents could push unwary boats into walls of ice jammed stationary across the strait. It turned out better than we had expected. The swirling currents did present rapidly opening and closing leads seeming to allow passage and then trapping anyone inattentive enough to be caught … but with effort the pitfalls could be avoided. We negotiated a lot of ice only to find ourselves blocked at Halfway Island, which is, as you guessed, halfway along the 13-mile strait.

While we hovered out of reach of the slabs of ice drifting by in the current, Claude offered the thought that if we waited, perhaps all the ice would pass us by. Repeatedly we backtracked to ensure an escape route was still open behind and then advanced back to the ice barrier. At each iteration, the water behind became clearer while the ice ahead receded with the tide to permit further advance down the strait.

|

|

Canadian yacht Acalephe and Swiss cat Libellule head for Willis Bay. |

Less than three miles to go

We were hopeful, but as the tidal flow turned we remained an impassable two and a half miles from the exit. The headlands at the end of the strait were right there, but they might as well have been on another planet.

During the slow return to our new truly ice-free anchorage in a bay west of Brands Island, we resolved to do the whole thing again at the next tide after perhaps three hours of sleep.

This repeat effort was an exercise in futility. The wind had shifted to the west and, surrounded by snow squalls, we reached the ice barrier right at Halfway Island as the turn of the tide approached. This was discouragingly short of our previous day’s mark.

On the 22nd there was a big west wind — obviously a no-go for the strait. But then we needed a rest, the engine needed an oil change and we wanted to go for a walk on the northern-most part of the North American mainland. And so another day of our fast-diminishing summer vanished.

That was the day the northern exit to Prince Regent Inlet started to block with ice. Most of us anchored around Bellot Strait were beginning to contemplate how we would winter over at Fort Ross — a geographic location with no settlement. The Dutch boat Tooluka and the British Arctic Tern succumbed to these thoughts and headed back north to return to Greenland. The rest of us just wondered what our personal date was for turning around. How long could we sit at Bellot waiting and still make it back to a port in Greenland before winter seriously set in.

A strong easterly forecast on the morning of the 23rd presented our penultimate opportunity to get to the west. So Acalephe and Traversay III set forth one more time in the middle of the night. These attempts were actually using very little of our precious and dwindling supply of diesel fuel. We headed west on a fair current and, if we failed to get through, we returned back to the anchorage with a considerable east-setting current after the turn of the tide.

This time we were blocked by ice with only half a mile to the western exit. As we pointed back east into the current with the ice wall behind us, our instruments showed us still moving west at nearly a knot. The ice blockage kept moving west as the last hours of west-going tide played themselves out. The Swiss catamaran Libellule joined us in our early morning vigil. In the end, perhaps 150 feet of ice separated us from freedom. In calm waters, we would have tried to push through, but in the swirling tidal currents, it would have been very dodgy. The ice was seven feet thick. There was even a large polar bear standing on it.

|

Ice blockage in Franklin Strait. |

|

The route to Cambridge Bay opened up on Aug. 25. |

A trump card

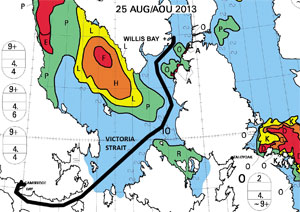

But we had a trump card that day. In the distance to the east we could see the Canadian Coast Guard icebreaker Henry Larsen steaming westbound through the strait. Behind, in line astern, were the icebreaker’s two charges: a cruise ship and the superyacht Lady M II.

After its primary duty was done, Henry Larsen came back and cut a short path through the ice just for us. Larsen’s 65,000-hp on tap slid it through the seven-foot-thick pack as if flowing through water.

Larsen was only just through into the clear water on our side when we all advanced our throttles and charged into the rapidly closing gap. Acalephe was first and had an easy time of it; we were second and slalomed around a few Volkswagen-sized pieces of ice. All the while I could hear Libellule behind me yelling “Faster, faster!” The ice was closing back in. Some large chunks bounced off Libellule’s stainless-sheathed bows, but it could not be helped; we were already going as fast as we could. And suddenly we were through.

But what had we done?

As the blue-sky day wore on, we explored the entire 20-mile width of Franklin Strait and found no gap, no obvious crack, in the white sheet to the south. Henry Larsen offered encouragement and helpful advice about routes, but thin ice to an icebreaker was not thin ice to us. Additionally, a northwesterly gale was coming and we needed a place to hide. It had to be on the west side of Peel Sound or Franklin Strait because anyone on the east side was going to be crushed by gale-driven ice or, if the hiding place was very good, merely be frozen into it.

Just as the wind started to blow, we dashed into Willis Bay — on the east shore of Prince of Wales Island — and anchored. We used too little chain, anchored in too-deep water and failed to keep an anchor watch expecting the anchor alarm to do the job for us.

At this point, because sometimes there is only one solution to a problem, there were five boats arrayed around the windward shore of the bay: Canadians Acalephe and Traversay III, French Isatis, Austrian Belle Epoque and Swiss Libellule. Isatis and Belle Epoque transited Bellot the tide after us and after a very cursory search for the non-existent route south, came into the same bay to hide from the coming gale. They had needed no help from an icebreaker and reported that Bellot had cleared out completely.

The wind blew, as gales do, and made a lot of noise. No one aboard heard our anchor alarm; it is much softer than the one we used to have. But, bless his heart, Nick on Acalephe was standing watch and called on the radio in a loud persistent voice that we were not where we once were, but halfway across the bay.

The waves were very large in the gale winds that far off the shore, and reanchoring in the cold wind and snow was a bit of a trial. This time we anchored close to the shore in shallow water and used all our chain. We even set an anchor watch.

Late in the season

The calendar had reached Aug. 24 and the way south was still blocked, the route north through Peel Sound was also blocked and Prince Regent back through Bellot Strait was nearly so. We still had faith, but wondered whether the boats heading back toward Greenland were perhaps the clever ones. Every day we were keeping warm with diesel out of the same tanks needed for propulsion. Some of the boats were beginning to hint at unhappiness with their remaining supplies. The nearest fuel was 300 miles away at Cambridge, Gjoa or Taloyoak, all on the other side of the ice.

By mid-afternoon on the 25th it was still blowing a gale as one by one the boats received the latest ice maps from their various sources. Libellule had fleet broadband; the rest of us relied on e-mails of compressed images sent by various friends. The maps, though, really all showed the same picture. Victoria Strait, the shortcut toward Cambridge Bay to the west of King William Island, displayed a usable path through the ice.

Finally it was time to go.

Thirty-six hours later we were still broad-reaching towards Cambridge Bay at more than seven knots. The ice was all behind. The watches were now inside, crew peering warmly through the windows. The sailing winds had banished all fuel worries. Nome was still many miles ahead at the far end of the continent, but we would be tying up there in a few short weeks. We didn’t know it at the time, but all five boats had made it through the worst of the ice!

————

Laurence Roberts and Mary Anne Unrau have sailed more than 90,000 miles in Traversay III, a Waterline 43 designed by Ed Rutherford and built of steel at Sidney, British Columbia, in 2000. They have crossed every meridian and reached latitudes from 65° S on the Antarctic Peninsula to 80° N at the northwest tip of Spitsbergen.