In 1974, I got the sailing bug and purchased a 25-foot Ericson sailboat. I renamed her Foot Loose. My U.S. Naval Academy classmate, Pete Mellin, and I were young naval aviators stationed in Pensacola, Fla. Early in 1975, I saw a flyer promoting a race to Cozumel in April. The race involved large, expensive racing boats and was sponsored by the Southern Ocean Racing Conference (SORC). The minimum size allowed to enter the race was about 35 feet. Well, I figured that my 25-foot boat was pretty close to that, and I went to see my classmate, Pete. I think I started the conversation something like, “How would you like to sail Foot Loose to a place where there will be lots of parties with beautiful women?” That immediately caught Pete’s attention. He then asked, “Where are we sailing?” I said, “Cozumel.” Pete asked, “Where is that?” To which I replied, “I don’t have the slightest idea.”

Planning and preparations

Cozumel turned out to be a sleepy Caribbean island off the coast of Yucatan just beginning to develop into a huge tourist resort. We were banned from the SORC race but decided to sail there anyway and crash the sailing parties. However, problems began to surface. These issues were brought to our attention by more experienced sailors in the marina. Here are just a few of the concerns that they raised:

• Foot Loose had no lifelines.

• There was no two-way radio, so how would we get help if needed?

• We had no engine in case the wind died or the sails were ruined, and we couldn’t charge our batteries.

• There was no bilge pump.

|

|

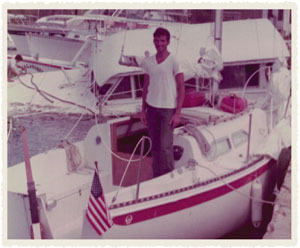

Foot Loose was an Ericson 25 with minimal electronics and nav gear by modern standards. |

• The boat had no life raft on board.

• We had no deepwater sailing experience.

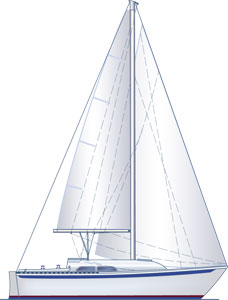

• A centerboard boat like ours was not designed for deep water.

• The lack of navigation equipment — the boat had no depth finder, compass, chronometer or knot meter. How would we navigate? In 1975, there was no GPS.

With less than three months to prepare for the trip, Pete and I spent many free hours working on the boat. We resolved most of these issues and ignored others. For instance, we bought a VHF radio good for line of sight range, about seven miles. However, we would not be able to communicate with land sites for about 97 percent of the voyage. After installation of lifelines and a 15-hp inboard engine, the next purchase was a small, manually operated bilge pump. This pump would prove extremely useful for our voyage. For navigation, a compass and knot meter were also installed. Pete and I decided to skip the depth finder and use a lead line for measuring depth. We tied knots in the line every foot and could estimate the depth of the water once the lead hit the bottom.

Since we could not afford fancy navigation equipment, we would try celestial navigation. So, our next acquisitions were an inexpensive Timex watch and a cheap plastic sextant with questionable accuracy — especially if the plastic were to be bent, broken or melted. Quality sextants were made of brass and much pricier. Pete and I also thought it would be a clever idea to bone up on our celestial navigation skills learned in Annapolis. We naively thought, “How hard could it be to use a plastic sextant on a small rocking sailboat?”

After looking at prices for life rafts, I decided to beg a Navy squadron chief petty officer to let me borrow two small naval aviation life rafts. He finally agreed but threatened to kill me if I did not return them.

As far as deep-sea experience, Pete and I figured that we would acquire that on our way to Cozumel. Now, the issue about Foot Loose not being designed for deepwater sailing was handled very delicately: We thought it best not to tell Foot Loose about this. That way, she would not lose her enthusiasm for the trip. Numerous other planning issues arose, and as the old salts continued their barrage of concerns, our optimism began to dwindle. Then, my insurance company abruptly cancelled my boat policy when I asked if they would cover the trip. Our low point was reached when these experienced sailors asked us if we had wills.

|

|

|

Plans for the Ericson 25 Foot Loose. |

The voyage begins

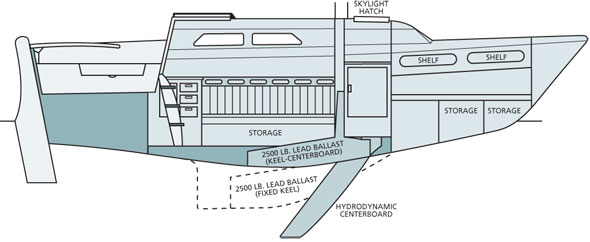

Cozumel is 600 nautical miles south of Pensacola. With decent winds, we hoped to make more than 100 nautical miles a day. We figured that the trip could be completed in less than three weeks — the duration of our authorized Navy leave. We planned a maximum of one week to get there, one week on the island and one week to return. As it turned out, we were not able to get Foot Loose ready for sea when the SORC race started from Biloxi, Miss., on April 19. We didn’t even have time for a sea trial in the Gulf of Mexico to check out all the new equipment we had installed. Nevertheless, we were determined to go and hoped that we would still arrive in Cozumel to catch a few of the last parties. So, one day after the SORC race had started, we were finally ready to get underway on sail power. On the day of our departure, April 20, the sky was totally overcast. As we left the channel heading into the Gulf of Mexico, we encountered a storm. We changed out our genoa sail for a smaller working jib and put a reef in the mainsail. Foot Loose seemed to be enjoying her maiden voyage into the Gulf; the crew was still uncertain.

The next several days of our cruise involved challenges such as a leak around the propeller shaft. Leaks have a way of getting the adrenaline flowing, especially if they can’t be controlled. Pumping the bilges of Foot Loose was something we had to do every few hours. After three days of pumping bilges, we decided to attempt an at-sea repair. Pete “kindly” offered to hold my feet as I squirmed past the Volvo engine with some tools. We were able to arrest the leak. With the exceptions of two more storms, we had relatively dry bilges for the rest of the voyage. That purchase of a cheap bilge pump had a wonderful return on investment — it kept us alive.

As far as navigation, we relied heavily on dead reckoning. This navigational method was essential when celestial bodies could not be seen due to overcast. We were unable to attempt a celestial fix until the second night when the skies cleared. It was at that point when we broke out my cheap Timex watch and the flimsy sextant to measure four stars. After plotting our data on the chart, we estimated that Foot Loose was somewhere south of New York City and north of Rio de Janeiro. We were lost. After this initial attempt at celestial navigation, we vividly remembered another issue raised by the experienced sailors in Pensacola: Cuba is quite close to Cozumel. In 1975, Cuba and the U.S. did not have friendly relations, and in fact, there were quite a few Americans rotting in prisons for entering Cuban waters.

When we were not worrying about Cuba, storms, navigation or the floatability of Foot Loose, there were special moments that made sailing so captivating. The sea presented amazing opportunities to appreciate its beauty. During pleasant weather, we loved watching the dolphins play off the bow. Another denizen of the deep, the flying fish, made its entry into our lives; we were amazed at how fast they flew in the air. Three hundred miles from land, a small split-tailed bird landed on our cockpit. It must have been exhausted trying to migrate across the Gulf. It seemed friendly and even hopped on our hands as we tried to feed it. However, after one day of rest, the poor feathered creature passed away and was committed to the deep. Another larger white bird spent a night with us on the bow. It slept standing on one foot and left early the next morning. Besides the birds and fish, there was considerable beauty all around us. Whether it was in the strength of the sea in a storm or the calming sunsets, we were in awe of Neptune’s realm.

|

|

The voyage of Foot Loose across the Gulf of Mexico. |

Strengthening a friendship

A daily routine for watches, meals and navigation developed. For example, we put two gallons of water on the deck each day to warm up in the sun for drinking and cooking. If any water was left over, it was used for a very short navy shower. Getting the salt off was great, but the last one taking a shower as the sun set was often shivering in the trade winds. One thing that Pete and I noticed was how this trip bonded us even closer. With four years at Annapolis, you develop very close friends, and Pete was one of my closest friends. After graduation that friendship continued, as we were both assigned to the same destroyer squadron in Long Beach, Calif. Our next joint experience was going through naval flight school. After receiving our wings, we were then both stationed in Pensacola. Our friendship was critical to both our enjoyment and survival of the voyage.

As Foot Loose approached the sea lanes leading to New Orleans and Houston, we expected to see more ships. During the third night, we remembered an old naval adage: A steady bearing and decreasing range means a collision is imminent. As a large cargo ship continued to get closer and closer, we unsuccessfully attempted to contact the ship on VHF radio and get their attention with lights. We frantically altered course. As the behemoth approached ever closer, Foot Loose barely avoided being smashed.

Second storm and grounding

On our fifth day at sea, the sighting of land was anticipated. Sure enough, the Yucatan Peninsula came into view. We also saw fishing boats hightailing it back to port to avoid an approaching storm. Knowing that we had to head east to get around the Yucatan Peninsula into the Caribbean Sea, Foot Loose beat into an easterly wind. Adding to this challenge, the western portion of the Yucatan Current was pushing us west. The storm winds on our wind meter were measured at 32 knots with gusts of more than 40 knots. As Foot Loose was heading into a strong current and heavy wind, the storm drove us backward to the west. After hours of fighting the weather, we were desperate. We started our engine for the first time on the cruise and doused the jib while heading closer to the coast to see if the current would ease off.

|

|

A sunken boat at the marina was close to where Foot Loose was tied up. |

As night approached, the search for Mexican lighthouses began. There was hope that they would help give us a better fix than the dead reckoning we had been using for more than 24 hours due to the overcast. None of the lighthouses could be identified, but our lighthouse reference had a warning that some Mexican lights were not very reliable. We hoped that our estimated position was relatively accurate, but at 2300 Foot Loose went aground. Although our dead reckoning fix on our chart indicated we were in deep water, the rudder had struck hard. Plus, a piece of the transom fell into the Gulf — that gave us some concern for water pouring into the cockpit. The rudder was bent at the waterline and flopping back and forth in the waves. We decided that it would be best for us to anchor for the rest of the night. We were exhausted and went right to sleep.

The next morning, the weather was beautiful. While we were still anchored, a Mexican fishing boat approached us. A man in the bow asked us in perfect English, “Where are you from?” We said, “Pensacola.” When we asked him where he was from, he told us Nantucket. His name was Robert. He was visiting the island with his girlfriend and was able to translate for the fishermen, who were from the nearby island of Holbox. The fishermen suggested that the island carpenter might be able to repair our rudder.

We limped off to Holbox and went ashore. We had no idea what to expect. We discovered the islanders wore no shoes. They had no phones and limited electricity. Many of the women were topless. The islanders spoke a form of Mayan intermixed with Spanish. We thought we were in a land that time had passed. By midafternoon, the island carpenter, Henry, had built cedar splints to stop the rudder from waving back and forth. However, he could not drill through the stainless-steel insert plate in the rudder with his hand tools. Thankfully, a Mexican army construction team was on the island building a school. They had a generator and an electric drill, which they let us borrow. With rusty bolts and nuts, Henry was then able to attach his splints. Our rudder was as good as new.

That evening, the islanders hosted us for a special dinner. Pete and I were simply blown away by their kindness. After much tasty food and thirst-quenching cervezas, the fishermen began to tell their own sea stories. They fascinated us with their sagas as they showed us the jaws of huge sharks they had caught. That evening we presented gifts to the islanders for their wonderful help. Early the following morning, Foot Loose got back underway, and we felt lucky for having gone aground and grateful to the Mexican army and the folks on Holbox Island. They were wonderful.

|

|

Drying laundry on the lifelines while at Cozumel. |

Cozumel

We finally caught sight of the northern tip of Cozumel on the following day. By 1600, Foot Loose entered the marina. Shortly after our arrival, we discovered that there were still two racing boats left in Cozumel. These remaining sailors were preparing for the return trip to the U.S. One of the boats invited us to dinner to hear about our voyage. They were amazed that little Foot Loose had made it to Cozumel, especially when they heard that our navigation was handled with a plastic sextant.

Pete and I enjoyed Cozumel over the next six days. However, our first priority was to repair assorted items on Foot Loose. We did a diving inspection of the hull that revealed there was no damage to the boat from the grounding. Our morale was again quite high.

Return trip

As we started our return trip, Pete and I were delighted to see Foot Loose exit the harbor and sprint at almost 9 knots over the ground thanks to a great wind and a fast-moving current. By the next day, Foot Loose was almost halfway across the Gulf. We began anticipating an early arrival in Pensacola. However, the Fates had other ideas in mind.

The winds began decreasing the following day, and Foot Loose slowed her breakneck pace. We hoisted the spinnaker to regain some speed, but shortly after this gain the winds died down to nothing. Halfway across the Gulf, Foot Loose had come to a screeching halt. With the sea like glass, it was damn hot. That evening, Pete insisted on turning on the engine to make some headway. However, with only 10 hours’ worth of fuel, we turned off the engine the next morning to conserve resources and we prayed for wind.

|

|

Visiting a local bakery to pick up supplies. |

Foot Loose remained without wind for another full day. Both Pete and I resorted to promising to attend church regularly for just a few knots of wind — I even volunteered to donate to the collection plate. We continued to try different sail arrangements in the hopes of squeezing out an extra tenth of a knot. By the afternoon, the winds slowly started to pick up, and the crew’s morale arose accordingly. Foot Loose was making a decent 4 knots. We were cautiously optimistic that our prayers may have been heard.

On our fifth day of our return trip, the Fates reminded us that they could take away the wind as well as make it howl. The first mate reported a sharp drop in the barometer — a sure sign of severe weather to come. We began hearing radio reports of a storm with a squall line. We realized that our prayers for more wind were going to be answered in spades. Pete and I began preparing Foot Loose for her third major storm. With winds picking up, we reduced sail, set up our safety lines and donned our life jackets, safety harnesses and foul weather gear. A log entry tells the story:

“May 7, 1975, 20:15 — We are in it now; thunder cells moving over us. The wind, lightning bolts and thunder are incredible. Lightning flashes illuminate the entire sky, all 360 degrees, and it is so bright I feel we might go blind. Wind screeches at around 50 knots, spray is horizontal, waves high. Foot Loose is riding the seas extremely well, and we both have great faith in her. Skipper is working his fanny off on the helm (it’s about time).”

After the storm, I told Pete I thought we experienced a waterspout. We only had the storm jib up, and I was trying to keep the boat relative to the wind I felt on my face. The boat was heeled over at a large angle with part of the deck in the water. I could see the compass spinning rapidly as Foot Loose made circle after circle. After the waterspout passed over, we were able to ride the storm more easily. We reflected on the power of the sea; the words “gratitude” and “alive” were at the tip of our tongues.

We saw the lights of Pensacola when Foot Loose was about 18 miles out to sea. By 0600, we were back at the dock.

David Charvat is a former naval officer and pilot who flew A-4 Skyhawks. He later worked as an environmental engineer and taught at Youngstown State University. Now retired, he works as a professional magician.

|

|

A view of Cozumel in 1975. |