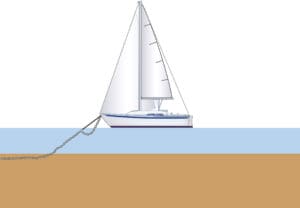

Have you ever been in an uncomfortable at-anchor situation? A fisherman friend told me once that anchoring is about 70 percent of boating. Maybe, for some people, but I see a lot of folks sweating it out, and a lot of boats bumping and/or crashing into each other. How could this be? Little or no experience – the test first and the lesson afterwards and we live and learn. Here are some thoughts on anchoring that voyagers can take to heart.

Once while anchored on a voyage, I had to confront just such an unexpected anchoring situation. My mariner’s eye gauged the rate of movement of my vessel, and determined it was dragging. My mind factored in imminent daylight and rising tide levels, etc.

The GPS showed us about to go on the beach, and had us picking up speed too as we skidded along the bottom. Start the engine! Roger. It started. I always thank God when that happens! Propellors can get fouled. Things go wrong. But the sails had been uncovered the night before in case of a problem. People survive by sailing, too.

The intertidal zone was now beneath us on the starboard side. The nice sailboat with the family on it was on our port side. It was blowing about 35 knots from west/northwest. There was the dreaded zig-zag pattern on the GPS screen.

After hauling up the mizzen I put my ketch in gear and throttled up a bit to make way and relieve pressure on the chain and take strain off the windlass, which, unfortunately, jammed almost immediately. The screw driver I needed to clear it was down below. I corrected the helm and eased the throttle en-route, twice. I steered slightly to port to get the smaller anchor along the starboard side and on deck.

Glad I hadn’t used a kellet! It was a 14-lb. Lewmar Delta on about 50 feet of chain. The boat was a bit wild and I had to keep running back and forth to keep pointing up, spinning the wheel and goosing the throttle. Oh, and get the big screw-driver to free the seized chain in the windlass.

This was a lot of setting land-speed records on deck, all teak like the rest of my old wooden boat as I ran from bow to stern and back. Then I had to remove the snubbers. I use 3/8-inch lines (two) with stopper knots through the links to bridle around the bobstay.

The mizzen was using the wind to help us point. Unbelievably and suddenly heeling over, the bow began to swing to port. Good because that was off-shore, bad because after a U-turn we’d be bearing down on that nice other boat that now seemed right there. At least we were getting into better depths now, a good thing because the anchor was still down there near the bottom and just not on it. No time to get it to the top.

I dashed back to the helm and dodged the other boat, spinning the wheel hard to starboard. I resumed my course out towards the main channel and more sea-room.

When re-anchoring, I paid out a lot more chain, and longer snubbers. The ship was happy and I was happy. The sun came out and the wind seemed friendly and warm, shimmered across the little white caps. Birds hovered in the air. Ah, the good life.

Those who have dragged

Chapman Piloting and Seamanship calls anchoring an art, meaning that there are sufficient variables for a person to truly express themselves with ground tackle. I’ll present some concepts that have worked well for me, now that I’ve demonstrated that there are two kinds of sailors: those who have dragged, and liars. That was not the first exciting dragging moment I’ve had.

I use a 45-pound Bruce on my eight ton (net) ketch. There is a swivel — shackled — and then a chain, 3/8-inch, with about 300 feet in the chain locker. When arriving in the area where I currently anchor, a local told me the recipe: “To the bottom and then two boat lengths.” This seems to work around here where people like to anchor very close to each other, which I found difficult to get used to. The regular depth is about four fathoms plus or minus tides.

My ship is 41 feet long overall so that’s about 106 feet of rode plus the snubbers, normally about 14 feet. We thus arrive at 120 feet of rode, about 5:1 scope ratio. This is normally adequate in sheltered waters without swells but in the above scenario it was not. Seven to one would work better.

In the above situation, I ended up paying out 170 feet in the end at my new anchoring location and did just fine.

It is officially the catenary action that holds a boat to the bottom and not the anchor size. I have proven this to myself in heavier weather with my bigger 50-pound Rocna anchor, which dragged without sufficient scope. Also: if you don’t have an all chain rode, you need at least some decent amount of chain before your anchor line, and a lot more line.

If you are anchoring in an unknown roadstead, an all-chain rode will prevent myriad stuff lying around on the invisible bottom from cutting right through a line rode while you sleep (and then drift) away. I’ve seen a lot of 27-foot sloops wander around and finally go off to meet their destiny because their anchors with rope rodes never reset in calm conditions.

If there’s a swell or any kind of a significant breeze I like to use snubbers: braided nylon that goes at least below the water line and sometimes all the way to the bottom. Use the biggest line that will fit through the link for handling ease and stretch. The smaller ones will explode after being banjo tight. The snubbers absorb the shock load and help keep the chain angle lower, increasing the catenary, as well as assisting the ship in tracking if your chain roller is off-set. They also remove the load from the roller on a bowsprit, and diminish hobby horsing.

Secure the chain

Use a chain hook to secure the chain, always. You need to have the chain firmly held in place so you’re free to do other stuff. I’ve seen people with horribly mangled hands and who have also been almost pulled over-board by freakish, sudden loads. Weird and scary. The hook keeps the load off the windlass. Speaking of seizing: use stainless wire to secure shackles and pins and then mouse them. That means no points/meat hooks poking out to rip through your skin suddenly when handling the rig. Same with cotter pins. Curl the ends around to hide the points. Run your hands over everything after you think your done and ask yourself: is this smooth?

After you think you’ve studied the possibilities and rules (Chapman’s is great!) and have the appropriate implements of anchor security, go out and start practicing. You should ultimately be as comfortable as parking your car. This means if you drop the hook in a less than ideal location, try again ASAP. Don’t save it for later. Don’t sit around wondering if that boat is too close.

Here’s how I do it: sight out an appropriate spot and not too close to anyone either. Quietly and slowly move upwind to that spot and stop, bearing in mind that you will fall off the wind after letting your anchor go. Pay out the rode easily as you gain sternway across the bottom, and not all at once. When the anchor hooks you will point up wind. Let the engine (if applicable) reverse you back easily to snub the hook. Don’t give it full throttle or you can be there all day wondering why you’re not staying put. Let the anchor settle itself.

Then go forward and attach the snubbers and let out more chain (if applicable) for a sag loop until they are tight. Tune them so they are even on each side after running them through fire-hose or anti-chafe gear at the hawse holes or wherever they run over the deck. Seize them with twine in suspect weather. Put the chain hook on to take the strain off the windlass. Be proud and feel good about yourself and enjoy the scenery. You did it. Take some bearings and pay attention to things until you are confident that the boat is secured to the bottom.

I’ve seen a lot of crazy things involving people and anchoring. Don’t speed along and tumble the hook overboard and then troll around like a bee looking for a flower. Throwing an extra anchor overboard (as mentioned above) doesn’t really work except to buy you some time. Even this is debatable since you lose time recovering it. An anchor much too big or much too small is a problem at best. Anchors don’t properly scale up but become entirely new situations with the increase of size.

Be prepared in advance for problems and be proactive. You’d be amazed at how things can get tangled, caught, or wrapped around absolutely anything. Even on a small boat, this is no joke. Pulling up an old, discarded bicycle covered with barnacles can weigh hundreds of pounds and add a few hours of fun to your morning schedule, not to mention cut you.

Anchoring as forgiveness

Finally, be a human being about things where other people are concerned. If someone is crashing into you, don’t go off on them. Get involved and try to assist if possible. It could be you. This is a chance to practice forgiveness and be the person you want to be. We all have to start somewhere. I’ve made friends after such tests of tolerance and understanding. And if not, let it go.

If someone anchors too close to you, be diplomatic and/or pull up your ground tackle and go elsewhere. It’s not worth the argument no matter how right you are. You’ll be glad as soon as you start pulling up anchor. There will be times when you may not have that luxury.

There is a lot to cover here, I know, and this is just one perspective. Read, ask questions – especially in foreign waters: seek out local knowledge! Edify yourself and then get out there and go boating. Get the experience and challenge yourself in areas where you are unsure. Don’t just get by with bad habits only good for your little routine, in your little world.

It is a paradox that you can only test your gear in demanding situations but you can use nice and easy weather to get familiar with things and get your hands in shape; try and see what works and what doesn’t. Then when you’re dragging on a lee shore and close to hitting another boat in a storm, you might somehow get through it and even make it look easy.

Using the example above, later that day the owner of the other boat came over, an ex-tugboat captain. I asked him if he saw what happened (of course he did) and if he found it somewhat entertaining (ditto). In fact, the day before I’d dinghied over and told him about the forecast, which he thanked me for, and then he left and came back, brought me some rum and a few other niceties. We became friends and shared worse mishaps, survived, and then he cruised off with his family and now I have a friend if and when I ever get to his harbor.

So get your skills together, maties. Be sober and diligent. Don’t be scared, be prepared. You’re captain! Take some courses. Know your boat. Your crew will appreciate it, as will the rest of us. Happy anchoring and have happy endings! ν

Daniel Carrigan is a writer, a sailor and boatowner, a singer-songwriter, multi-instrumentalist musician and a music producer. He lives in San Diego.