Sooner or later anyone who relies on navigational charts finds mistakes. The “magenta line” for the Intracoastal Waterway takes them aground. That shoal is actually 100 yards from where the chart says it should be. Or the chartplotter depicts your boat actually moving over land somewhere. Most of these cases are errors of measurement, and they usually involve underwater features.

There is, however, an exception. It is an unusual case in which the world’s most prominent mapmaking agencies have failed to acknowledge the disappearance of an entire island, and, although not very big, Jackson Cay is not without historic and practical significance.

Each year, hundreds of cruisers voyage to the Caribbean the hard way. Their numbers include Canadians and Europeans, but most of these recreational mariners hail from the U.S., many of them retirees. From Florida it’s a rough ride all the way to St. Martin, against wind, waves and current. And as any old sailor will tell you, the worst part of “the thorny path to windward” is the north coast of the Dominican Republic.

Christopher Columbus was the first foreign sailor to learn this lesson during his 1492 voyage to the New World. Columbus had to follow the thorny path as a necessary prelude to his return voyage to Spain. First he lost his flagship Santa Maria, wrecked on a coral reef off what is now Haiti. Then he had to find safe anchorages for his remaining two ships, Niña and Pinta, as they struggled to sail eastward against the trade winds. Harbors with good protection were often too difficult to access because of shallow entrances, and bays where it was possible to anchor were exposed to ocean swells from the north — likeliest during winter — creating possible death traps.

On Jan. 12, 1493, Columbus finally got a break. Borne by a brisk — and very rare — westerly wind Columbus’s ships, were “boiling along” as they drove eastward, according to naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison.

High up the masts, while transiting the north shore of today’s Samaná Peninsula, Columbus’s lookouts spied an island near shore between two points of land and against a mountainous backdrop. The low island rose out of a field of scattered reefs indicated by breaking waves. The lookouts would also have been able to see that a channel from the east led to the deep blue basin. Columbus named it Porto Sacro, Sacred Port.

Bartolomé de las Casas, the Dominican friar who wrote a contemporary account of the voyage based on Columbus’s diary, described Porto Sacro as “an immense and good port with a good entrance.” An 1853 map of Samaná would describe Columbus’s harbor as a porto fuerte (a strong port), recognition of the protection it afforded against ocean swells. Columbus, as it happened, never took his ships inside the harbor. The steady west wind was too good to waste.

Port Jackson

For most of the 17th century, French pirates used the big bay on the opposite side of Samaná Peninsula as a “place of rendezvous.” Later Porto Sacro acquired a new name, Port Jackson. The protective island became Jackson Cay; the headland on its east side, Point Jackson, and the high hills behind, Jackson Mountains. To this day, the half-mile-long rim of sugar sand overlooking the anchorage is called Jackson Beach. The ubiquitous, eponymous and acquisitive Mr. Jackson was likely one of 220 freed American slaves transplanted there in 1824 as part of a social experiment.

Throughout the Age of Sail ships called on Port Jackson to take on loads of coconuts and to fill barrels with drinking water from a spring-fed pool on the beach. However, by the first half of the 20th century Jackson had fallen into disuse, rendered obsolete because overland access was nearly impossible by any conveyance other than pack animals.

On August 4, 1946 an earthquake measuring 8.1 on the Richter Scale hit Samaná, spawning a 12- to 16-foot tsunami that inundated lowlands. Quake and tsunami killed 2,550 people. Mini-tsunamis were recorded as far away as Daytona Beach and Atlantic City. The next day Jackson Cay was gone; the 52-acre island had sunk like Atlantis. A feature that had stood a few feet above the water was now a few feet underwater. Yet the mapmakers of the world paid no heed.

By the 1960s a revolution in boatbuilding — the advent of fiberglass construction — made yachting affordable for the middle class. That’s when more gringo sailors began transiting Dominican waters en route to Puerto Rico and the Lesser Antilles.

Cartographic cockup

To be sure, an island would form a better barrier against waves, but a shallow 52-acre reef (among scattered breaking reefs in deeper water) affords a modicum of protection from ocean swell like the atolls of the South Pacific. The problem: Over the decades nautical charts have continued to show Jackson Cay as if it hadn’t sunk. Finding the Port Jackson anchorage in the absence of Jackson Cay would present a multi-level puzzle to an average mariner, particularly before the era of GPS navigation.

Bruce Van Sant has transited the waters in question possibly more than anyone else alive. Van Sant is the author of A Gentleman’s Guide to Passages South: The Thornless Path to Windward. His book contains a wealth of science-based tactics for passagemaking on the north coast of the Dominican Republic. Puerto Jackson is not mentioned in his book, but not for lack of trying.

Port Jackson was noted on government charts he carried, and Van Sant recalls that once during the 1980s he searched unsuccessfully for the port, which, according to 1918 U.S. government sailing directions, had “depths of 5½ to 7 fathoms and affords shelter to moderately sized vessels.”

Barry Terry sailed across the Atlantic to the Caribbean in the 1990s and spent the next two-and-half decades cruising his 34-foot sloop up and down the Antilles and delivering other people’s boats to and from the U.S. On occasion he would use anchorages elsewhere along the north shore of Samaná that were less well protected from northerly conditions. “Cayo Jackson would have been a better anchorage if you were pushed for time, as most delivery skippers are,” he said. “It would make great overnight stop if you needed a break after crossing the Mona Passage, and it would not take you very much out of your route.”

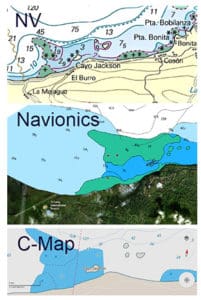

The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency calls itself the U.S. intelligence community’s “go-to agency for processing and analyzing satellite imagery.” Yet NGA provides charts to the U.S. Navy that still depict Jackson Cay, 76 years after it sank, even though its non-existence can be confirmed by a cursory check on Google Earth. The venerable British Admiralty also sells a chart that shows an island where no island exits, and the Admiralty’s current piloting guide to the Caribbean Sea gives highly specific directions on how to enter non-existent Port Jackson using the non-existent island as a landmark.

These agencies provide the data for private cartography companies that make electronic charts for the recreational boating market. Neither the NGA nor the Admiralty have been willing to help explain how this mistake went uncorrected for decades, let alone how it happened in the first place.

Ken Cirillo was a vice-president for C-Map, one of the top marine cartography companies in the world. Cirillo says he has no idea how the NGA failed to note the disappearance of Jackson Cay and why the Admiralty continues to describe Port Jackson as if it were an active port. In general, he says, charts are updated more frequently for high-traffic waterways. Port Jackson’s isolation and decades of disuse before the 1946 earthquake is probably the simplest explanation for the errors. Then, assuming no one complained, Jackson Cay’s disappearance would have been like the tree that falls in the forest unwitnessed.

Peter Swanson is a lifelong sailor and journalist, specializing in the Bahamas and Greater Antilles. His birthday is January 12, the date Columbus “discovered” Port Jackson.