My Pearson Electra, sleek as she is, weighs a little more than 3,000 pounds and is propelled by a three horsepower Torqeedo electric motor. I captain her along the May River in South Carolina’s low country, which stretches with miles of tidal creeks and rivers from Pawleys Island to the confluence of the Savannah River at the Georgia border. I’ve had no problem powering through the strong tides, what are regarded as one of the Eastern seaboard’s greatest differentials with surges of up to eight feet.

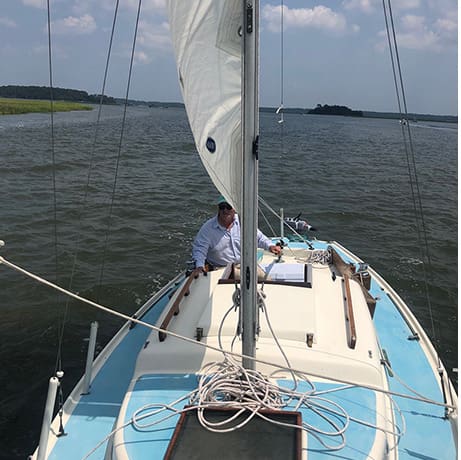

I fell in love with this 58-year-old boat, named Sea Gypsy, when I first spotted the online posted photos of her flag blue unblemished restored hull. Who could resist her curved bow, slender lines, forward canted transom, cozy-cuddy and full keel.

The boat market is riding a wave of renewed interest and booming sales during this health storm. The National Marine Manufacturers Association claims that sales of boats, marine products and services in the U.S. market in 2020 reached $47 billion. Among the new boat buyers are many who are responding to the advances in the electric vehicle market. That’s why my new Torqeedo Travel 1103 CS proved to be no exception. The lightweight high performance lithium battery, complete with onboard computer with GPS-based range calculation gave me confidence to step quietly into the electric revolution.

Some analysts have predicted that US sales of electric outboard motors alone may reach as much as $120 million in 2024. This bullish forecast belies the fact that for most boaters, electric remains a nonstarter, mainly because of the limited power of the battery. Besides, American boaters want to go fast and for them, there’s no such thing as a no-wake zone.

Sailing from a friend’s dock in Bluffton I’m greeted with tidal marshes, spartina grass, and an amazing array of flora and fauna with nearby nesting pelicans and egrets. Historic Old Town Bluffton emerged in the early 1800s atop its signature high banks along its beautiful May River. This coastal community offers cool southerly breezes off the scenic river. Today, this fast-moving body of water, spilling into Calibogue Sound, is interrupted only by the roar of gas-guzzling, high-powered speed and luxury boats gunning through the water, creating a wake that easily rocks my vintage 23-foot sailboat and disturbs the gentle dolphins that swim in these tidal waters.

I have learned that there are about 30 manufacturers of outboard electric motors and there are more than 40 brands of outboard electric motors available in the market. This popular upsurge in the electric motor market is motivated by a desire to address climate change and emissions by reducing pollution and noise. From my perspective, the Torqeedo fulfills that and more, since it eliminates any rising gas costs and messy cleanup. It helps that the motor is lightweight and easy to operate.

Since I choose not to leave my electric engine aboard, I carry it and battery in its own stylish carrying case and it weighs less than 35 pounds. The customized bag is about the size of a golf bag and the shaft fits perfectly inside.

As a part-time islander, I have recently renewed communication with the South Carolina Yacht Club at Windmill Harbor on Hilton Head Island. It’s home to many of the island’s wealthiest residents, many who are retired multinational CEOs. The club also has a specialized race class of Harbor 20 sailboats.

“Yes, we have Wednesday evening regattas and have a fleet of Harbor 20s and some of them are outfitted with Torqeedo electric engines,” says Mark Newman, the South Carolina Yacht Club sailing instructor and director of the club’s yachting program.

He’s quick to add that these older electric motors struggle against the tide and often make very little headway. But he also notes that the builder did a poor job adapting the motors for use in the well of these boats.

Other club members, like Ted Arisaka, an ardent blue water sailor, also believe that the electric motor has a mixed record. “When they work, they provide good thrust.” Since the battery was placed in the starboard lazarette, the battery pod, which has a GPS does not get a good view of the sky and so some of the advanced features, like estimating remaining distance available are not functional. “The battery is set up to be recharged in the lazarette with a non-watertight charger connection.”

However, there’s agreement among users that the electric engine is quiet, dependable without any flammable liquids, or petroleum spills in the water and no exhaust fumes. The refrain is clear: no more changing the oil, filters and bleeding the system for those with electric motors.

There’s a wide range of attitudes among sailors who are adopting the electric motor. But the science does not lie: a life cycle assessment of electric- and gasoline-powered pump-out boats reveals that electric boats have lower lifetime greenhouse gas emissions than do their gasoline-powered equivalents. This is particularly true when electric powered boats are charged using renewable resources, like a solar panel or even a wind generator.

As for my situation, I decided to install a 50-watt solar panel on Sea Gypsy and although it’s slow and drawn-out process for fully recharging the battery on board, I am able to recharge while on the water.

While range is always an issue with this setup, Lyall Burgess and his wife, Katie and their company, Sun Powered Yachts, located in sunny Hawaii make terrific solar panels. Now, it can be a bit tricky wiring a non-Torqeedo solar panel but a small adaptor cable MC4 does work since the battery has a built in MPPT controller that regulates the flow of power from the panel to the battery. I generally take my battery with me when I leave the boat and recharge it at home.

The winds of change, triggered by this electric revolution will certainly be powering me without a carbon footprint into the next stage of my sailing life.

James Borton, is an environmental policy writer, author and senior fellow at Johns Hopkins University’s Foreign Policy Institute in Washington, D.C.