manifold, which supplies raw water to multiple HVAC condensers. The bonding wire, while not harmful, will provide no cathodic protection as the manifold is much too far away from any sacrificial anodes.

Most marine air-conditioning units rely on seawater for their operation. The pumps and plumbing associated with these systems can pose a significant flooding threat, one that is exacerbated by the sheer volume of hose that is required to plumb the average cruising vessel’s condensers. For these and other reasons detailed below, HVAC raw water systems benefit from close scrutiny.

Air-conditioning 101

Air conditioning systems aboard most boats rely on raw or seawater to cool down pressurized, hot refrigerant after it leaves the system’s compressor. Via a heat exchanger or condenser, the seawater absorbs heat from the refrigerant, heat that has been created as the gas is compressed within the unit’s compressor. In the process the refrigerant is both cooled and condensed into a liquid. The cool, high pressure liquid then enters the evaporator, passing through a small orifice. As it does so the pressure drops, it turns back into a gas or evaporates, and in the process is able to absorb heat from the cabin — heat that it then later passes on to the seawater flowing through the condenser. The process works in much the same way for refrigerators and freezers. The hot air that blows on your feet when you stand in front of many refrigerators is heat that is being removed from the condenser.

For household air conditioners the same process occurs with one exception. Instead of seawater, air is used to absorb heat from the refrigerant as it passes through a finned radiator-like condenser. Aboard a boat the most readily available cooling medium, seawater, carries out this process. The benefit to this approach is efficiency: Seawater absorbs and carries away heat from the air-conditioning condensers, using a heat exchanger that is a fraction of the size of an equivalent air-cooled model, and no excess hot air is produced aboard the boat.

Risk of active flooding

The quid pro quo for using seawater for onboard air-conditioning and refrigeration systems is the risk of failure and subsequent flooding. Raw water must be brought aboard though seacocks, strainers and hoses as it travels to a pump. After it leaves the pump it travels to the metallic air-conditioning condenser, then through more hoses and to an overboard discharge fitting, typically above the waterline. For larger systems raw water manifolds are often involved, enabling a single pump to supply multiple air-conditioning units, as well as collecting water from multiple units for a single point of discharge.

Unlike most other raw water plumbing systems aboard, where water within hoses and pipes is “pressurized” as a function of how far below the waterline it is located — what’s known as head pressure — much of the plumbing associated with air-conditioning systems is under pressure. That is, once it leaves the air-conditioning raw water pump, it’s under pressure, and as a result a leak is no longer a function of head pressure, but of pump pressure. Hence a broken fitting can lead to what I refer to as active rather than passive flooding. Failures of air-conditioning raw-water plumbing have led to flooding and sinking while vessels were dockside. Their integrity, therefore, is of paramount importance.

Plumb for robustness and reliability

Plumbing used in air-conditioning raw-water systems must be designed and installed to ensure the greatest durability and reliability. Both material selection and the manner in which systems are installed must be carefully thought out.

Among the most common faults is the use of metallic plumbing that is unsuited for raw water applications, including brass and stainless steel. A few years ago a client contacted me and asked about installing a bilge drying system to remove incidental water accumulation. I asked, “Where is the water coming from?” “I’m not sure” he answered, “but don’t all boats have water in the bilge?”

In fact, while some bilge water accumulation can be considered normal – from a stuffing box or minor deck leak for instance – for the most part bilges should remain dry. In this case I encouraged him to hire a professional mechanic, who was tasked with finding the source of the water, which turned out to be a seriously corroded brass pipe nipple, thought to be bronze by the yard that installed it only 10 months earlier, that conveyed air conditioning raw water overboard. Whenever the air-conditioning system ran, which at the boat’s Florida location was nearly continuously, water shot sprinkler-like from the porous pipe nipple. Because it was behind a bulkhead, it went unnoticed, other than the water accumulation in the bilge.

Stainless steel, while highly corrosion resistant when afforded a ready supply of oxygen, can be a liability when used with raw water, particularly if seawater remains inside the pipe when the system shuts down. In this scenario, the water is quickly deprived of oxygen and as it evaporates the salt concentration rises, setting up an ideal environment for corrosion. Even the otherwise highly corrosion-resistant 316L alloys are not immune to such failures. I’ve encountered stainless manifolds that began to leak after little more than a year in service.

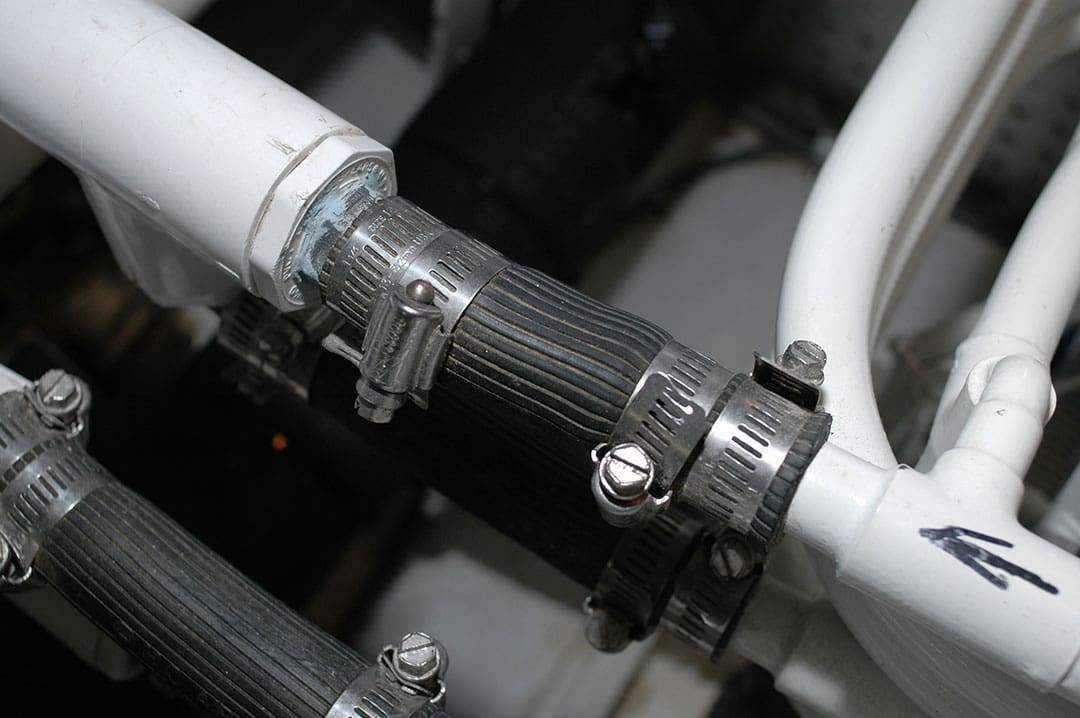

Yet another material that is ill-suited for air-conditioning raw water applications is PVC. While essentially corrosion proof, because of its potentially brittle nature PVC is less than ideal for raw water scenarios. I have accumulated a collection of fractured PVC components that serves as a reminder to avoid this material in raw water applications. Having said all that, in some cases it may be considered the lesser of two evils: Some air conditioning manufacturers use it for chiller raw water plumbing. If it is used only as part of a system supplied by an air conditioning manufacturer, installer or boat builder (for which they take responsibility), the CPVC and schedule 80 variety should be chosen for its greater ductility, crush resistance and tensile strength.

Above all else, plumbing must also be well supported, and while this holds true for all raw water plumbing, it’s especially true of CPVC. It should not support the weight of hoses or a large manifold, particularly large, thick-walled black EPDM hose, as they are both heavy and inflexible. Ideally, if used, a CPVC manifold should be fully supported on a backing plate or board, and use SEA J2006-rated silicone hose for all direct connections to the manifold itself. Silicone hose is lighter and more flexible than its EPDM brethren, and thus places far less strain on rigid plumbing.

There is a contingent of materials that are well suited for air-conditioning raw water systems. These include bronze (with a zinc content of less than 10 percent), fiberglass, glass reinforced nylon and SAE J2006-rated marine wet-exhaust hose. Provided they possess the necessary tensile strength and modulus of elasticity, non-metallic components are very desirable because the ever-present threat of corrosion and velocity-induced erosion is eliminated. Unless it is specifically rated for pressurized raw water applications, under no circumstances should clear PVC hose, even if reinforced, be used.

I find leaks and failures in air conditioning raw-water plumbing, especially corrosion, on an all-too-regular basis. My theory on why failures occur with such regularity is based on frequency of use. Compared to other raw water systems like engines, generators, heads and water makers, air conditioning systems run a lot more, especially in warmer climates with longer summers. The sheer number of hours they operate, and tens of thousands of gallons of seawater pumped by these systems, means their design and materials are often tested like no other aboard. n

Steve D’Antonio has managed boat yards and custom boat building shops and has written more than 1,000 articles. In 2007 Steve launched Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting, Inc. (www.stevedmarineconsulting.com), offering marine systems consulting, management and technical training.