Eric’s story: Debbie and I had been bashing our way east from George Town, Bahamas, for several days, heading to Turks and Caicos. With 30 to 40 knots of wind right on the nose, of course, and 8- to 10-foot seas, we were taking a fierce pounding in Indigo, our 46-foot Leopard catamaran.

With just 50 miles remaining from Mayaguana Cay to Caicos, and assuming that the wind would clock around to the east, our planned heading of 136° would mean that we could sail for the first time in many days rather than just motor. At dawn we navigated our way through the narrow, intricate passage of nasty reefs at the west end of Abraham’s Bay and headed southeast into open ocean for the next 10 hours.

Amazingly the wind actually did turn to 090°, and at a manageable 20 to 25 knots for a change. We hoisted full sails and were treated to close-hauled sailing at 7 to 9 knots for several delightful hours.

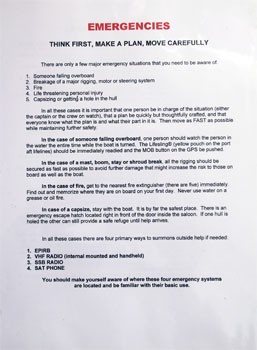

Emergency manual

Indigo has a detailed 30-page crew handbook that lists, among other things, all our emergency procedures. The evening before we set out, as we sat in our cockpit watching the sunset and savoring a well-deserved beer, Debbie and I had decided to go over our safety plan again. We discussed the four methods of emergency communication in the event of a disaster (SSB, VHF, EPIRB and satphone), where all the emergency gear was located (life raft, EPIRB, flares, radios, ditch bag) and lastly our man overboard (MOB) procedures: push the MOB button on the GPS, head the boat into the wind, try to keep the person in sight, throw the life ring attached to the MOB pole, turn on the motors (if not already on) and sail/motor to the person from a downwind position.

Debbie is pretty new to sailing — we’ve only had Indigo 18 months — so she wasn’t particularly confident about her ability to actually effect a rescue in real-life conditions, even though she had taken several ASA sailing classes with lots of MOB practice (mostly rescuing hats and cushions). In reality, no one is actually sure they can pull off a rescue in open-ocean, real-world conditions until the time comes.

Lastly, as the sun set and we headed to bed early for our dawn departure, we agreed that if there were any chance at all of getting tossed over the edge, we would always wear an inflatable life jacket and tether ourselves in. We practiced quickly donning life jackets and clipping into the lifelines. Everything was set for a tempestuous bluewater crossing the next day.

|

|

Eric and Debbie in port. |

Debbie’s story: We had left from George Town, Exuma, for the Turks and Caicos where we were scheduled to meet a friend in 10 days. Gale force winds and high seas to match were relentless, yet we pressed on. Every morning we were hopeful that we would get a different wind forecast, but to no avail. So, we did what we said we would never do and that was to try to beat the clock — big mistake.

Quoting the illustrious words of my husband, Captain Eric, “How bad can it be?”

Let me tell you, it can be bad. Really bad…

The prevailing winds were sustained at 36 to 42 knots from the east, so we knew what was coming — after all, we had “been there, done that” all the way down the coast of Florida. With a shrug of the shoulders we battened down the hatches and sucked it up. High winds on the nose equal big swells, no sailing, no following or rolling seas — just a bash-fest for hours on end.

I figured the sea god must have had an argument with the wind god and they were at each other once again like nobody’s business.

Halfway across the Caicos Passage the wind got increasingly fluky and we turned on one of the cat’s two engines to help keep our forward progress at a realistic pace since we did not want to enter the Caicos Bank after dark (the bank is seven to 12 feet of green water liberally strewn with hull-crunching coral heads and old wrecks).

A boat check

With the engine on I decided to do a quick survey of the boat, a constant task since we were taking such a beating. I checked a suspiciously wobbly SSB antenna and found that the connection to the upper bracket had come loose. Since it was around eight feet above deck level, and we were still pounding into 6- to 8-foot seas, I just rigged some shockles (like a bungee on steroids) around it and tightened them to the adjacent railings.

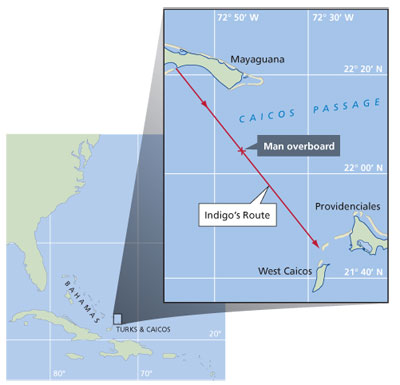

|

|

The man overboard situation occurred while on a passage from the Bahamas to Turks and Caicos. |

That’s when I saw it.

Looking down into the tender that hung from the big fiberglass davits on the stern, I realized that one of the four U-bolts that held tender to the harness had broken — meaning that the heavy, motor end of the tender was hanging by just one suspiciously weak U-bolt as we pounded along. Yet another fire drill on our eastbound odyssey.

I stared down into the tender as it shuddered and shook with each new wave that slammed into our bows, throwing spray clear over the top of the flybridge. How the heck was I going to fix this? Especially in these conditions?

The first thing to do was somehow secure the tender before the other U-bolt gave out. I grabbed a hammer and screwdriver, leaned over the transom and into the tender, and hammered the failed bolts out of the holes. Luckily they came out easily, leaving two holes that I could attach something to.

Now of course this was the moment when any sane person would immediately put on a life jacket and tether himself onto something secure — very secure. Unfortunately I have never been known as a sane person. Indeed, quite the opposite. One would need many extra fingers and toes to count the times that I should be dead: rock climbing falls, bicycle and motorcycle crashes, avalanches, ultralight and small plane crashes, downhill ski racing wrecks and, yes, I have even been hit by lightning. Twice.

Trouble follows

While I don’t usually go looking for trouble, it seems to follow me around, something Debbie acknowledges and accepts for some crazy reason. Thus she was up at the helm, holding the boat steady in the pounding seas while I was running around with a screwdriver in my mouth trying to figure out what to do next.

|

|

The emergency procedures page from Indigo’s crew handbook. |

|

Pat Rossi/Navigator Publishing |

Eric discovered that our dinghy was hanging by a thread (or I should say a broken bolt) and it had to be fixed immediately or we would risk losing it right off the davits. So he did what he always does, many difficult and dangerous moves preformed underway while I pray he doesn’t get hurt, or worse yet, fall overboard.

I found a stout eyebolt in my toolbox and decided that it might work. Back out to the tender where I again dove halfway into the dangling inflatable as the waves surged under the hulls and gushed up between the stern and the tender in a constant and violent drenching. Remarkably, I managed to get the bolt in place and the nuts fastened. Now I had to reattach it to the harness.

The 300-pound tender, laden with an extra 50 pounds of sea water in it and bouncing around like a beachball in a hurricane, was not about to be lifted up. I tugged as much as I could (the adrenaline released from the thought of losing the tender certainly helped) and secured a line from the bolt to a cleat on the davit. But it needed more.

I grabbed another piece of line with a carabiner on one end to hook to the outboard motor mount and secure to one of the stern cleats, then I deftly swung under the stern safety lifeline and out onto the middle stern step so I could reach around onto the motor. Yes, something that Debbie and I had agreed we would never do. But with adrenaline coursing through my veins and success in my eyes, I was indeed invincible.

Until I slipped.

Indigo lurched up over a swell and suddenly slipped sideways as another wave hit the hulls. The tender, still not completely secure, swung away from me just as I lunged for the motor. My wet hands hit the side of the lower motor and slipped off. In an instant, I was in the water.

|

|

The harness attachment point for Indigo’s tender. |

Complete shock

Those two seconds played out in depressingly slow motion as I went under water. I came up to watch as Indigo sped away, a feeling of complete shock taking hold.

“Debbie!!!” I screamed as loud as I could manage, at the same time thinking that there was no possible way she could hear me over the howl of the wind while sitting high up on the bridge. It was a cry of sheer desperation.

I was at the helm, we were doing about 8 knots and the seas were moderate compared to what they had been. Eric grabbed all the essentials needed to take care of the problem and he began to secure the dinghy with more lines. I took a look back on occasion to check on him and as he dangled out of the tender with tools hanging out of every pocket he seemed to have everything under control. In the back of my mind I was thinking how much I truly hated it when he did those things…

So, I resumed my watch at the helm, put my headphones on and enjoyed the ride. Then to my alarm and surprise I suddenly heard him call out loudly and desperately, “Debbie!!!”

Somehow she heard me.

She instantly turned around and saw me, a look of horror taking hold of her face. Here we go again. I watched as panic took over for a brief instant, then I could see no more as a big wave crashed over me and Indigo was lost from sight.

|

|

The broken bolt discovered by Sanford. |

I came up and waved frantically to be sure that she could still find me. To my utter surprise and relief she waved back.

Now I have heard my name called, my name yelled, and my name cursed by others in all kinds of tones and volumes, but not like this. I turned around and much to my horror Eric was in the water. I was stunned to say the least. Fear gripped me and I momentarily froze and just stared, I couldn’t believe my eyes.

I shook it off and ran to the stern. I saw him waving. My first reaction was, “WHAT THE HELL?” Then I finally began to process what I was looking at and what had happened. I waved back at him and went into emergency mode.

Panicked and shell-shocked, I stalled again for a minute while I tried to remember what to do. Things started coming back to me at what felt like a snail’s pace. I hit the MOB button on the chartplotter, slowed the boat, got the sails de-powered and checked on his location. In my flustered and frenzied mode, I thought I could get the jib down but there was no time for that and far too much wind. At this point I was beyond upset but kept saying to myself, “Get it together, get it together, I can do this.”

I could see him (he was visible because he was wearing a white shirt). A life jacket, unfortunately, was not on his scheduled attire that day — grrrrrr. But being able to spot him helped calm my nerves a bit even though I was going through so many emotions it was hard to think.

Turning the boat around

She hesitated a bit trying to figure out what to do, then did the exact correct thing: With the engine running, she turned the boat around and headed back to me. Ha! Cheated death again! Assuming she didn’t lose sight of me in the boisterous seas, that is.

|

|

The rear harness holds the weight of the tender and the outboard. |

I could hear him yelling to turn the boat around and I was ready to make the turn, but first I ran back to throw the life ring off the stern. I clipped the line to the boat but it was not long enough to reach anything, let alone a MOB 50 yards away and that made me very mad. (Note to self: I should have used the Lifesling).

By the time she got Indigo turned around she was already a quarter mile away. Trying to locate a head bobbing around in 8-foot seas in the middle of the ocean at that distance would present a mighty challenge for even the best navigator. As she neared me she jumped down from the helm, grabbed the orange life ring, tied it to the stern and threw it overboard. But in the big seas she was still 50 yards away and I couldn’t reach it. “Just head right for me and I’ll grab it,” I yelled.

Indigo once again disappeared in the swells and I was swimming hard as she swung around for another try. In her adrenaline-fueled state Debbie was going too fast and I couldn’t grab the ring. “Stop and boat and I’ll swim to you,” I yelled.

I made my way back to the helm and started what I thought was my “slow and deliberate” 360-degree turn, but as I was turning I lost sight of him because I was actually going way too fast. That horrible, helpless feeling rushed back in for a moment until I heard him call out, “Slow down! Reverse, reverse!” I followed his voice and instructions — extremely glad I didn’t run him over — and I saw him off the port side. I put Indigo into neutral and the boat slowed.

When the boat slowed, I swam, shoes and all. I grabbed the transom step and hung there for a second before I flung myself on board as another swell lifted the stern high above the water.

I rushed back to him, he could see the look in my eyes — too mad to cry, too scared to be pissed, and my adrenaline was off the charts. I kissed his wet salty face and collapsed back into the helm for a moment. Eric kept saying, “I’m OK, I’m OK, now get her (Indigo) back on course.” I was thinking, “Really? Is that all you have to say?” But I did it, just as if nothing had happened. I put her in gear, back on our line, and we headed off to Caicos.

Once I got back aboard, I wanted to say, “Hi honey, I’m back! Thanks for saving my life. And oh, what’s for lunch?”

|

|

Sanford demonstrates how he leaned into the tender to make repairs. |

The gamut of emotions that we both went through was unreal. Eric WILL NEVER EVER fix or attempt to fix anything underway again without his life jacket on and clipped on to a line attached to the boat!

Was this the end of it? Hardly. I travel with a man of adventure. A man who defies rules and doesn’t have an ounce of fear in his body. Needless to say, we never have a dull moment. There is always something happening, breaking or something going awry — it is a boat and he will take care of it.

A side note to all those who stand second in command, (the wives, the first mates): Only a week or two earlier a fellow cruiser had asked, “If something happened to your husband, could you manage the boat?”

I said, “Yes,” but with some trepidation, which led me to stop and really think twice about my skills and knowledge. So I asked Eric if we could go over our safety equipment and guidelines just the night before his swim in the big blue ocean. Ironic? You can decide, but I can proudly say now that Eric has taught me well and I can somewhat manage the boat. However, if he (my husband, my love, my captain) does something stupid like this again, I just might look back and wave.

A single chance

Had the circumstances been even a tiny bit different — had the wind been stronger or the waves bigger or had the prop had become fouled by a line — well, I’d be a goner. As I splashed around in the water watching Indigo sail away, a million thoughts flooded my mind. If she doesn’t hear my one yell — my one single chance for rescue — I’m dead. Gone. Poof, just like that. Even if she noticed me missing only five minutes later, the chances of finding me in these conditions was remote at best.

Instinctively I started swimming after the fleeing boat as soon as I hit the water. I remember thinking, gee, this water is nice and warm. Nice day for a swim out here in the middle of the ocean … too bad I’ll never make it home alive.

Many years ago I was in a small plane crash where two people died and the pilot was severely injured. As I lay in the hospital bed a friend came to visit. “Someone is saving you for something special; that’s why you’re still here.”

Not being particularly religious, I balked at the idea. Unless that reason is to show other people what not to do. Once again I’m alive and kicking after a very close call. All I know is that when I got back on board I put on my life jacket, clipped in my harness and stayed that way the rest of the day. I may be invincible but I don’t need to be that stupid ever again.

Eric Sanford and his First (and best) Mate Debbie Lynn have cruised together for seven years in the Pacific Northwest, Mexico and the Caribbean. Based out of Hood River, Ore., their “summer” boat is a 43-foot Ocean Alexander trawler while their “winter” boat is a 46-foot Leopard catamaran. Follow their adventures at www.facebook.com/indigo46.